by Ryan Cleckner

The three worst habits of unsuccessful long-range shooters aren’t what you might expect. They aren’t shooting techniques like improper trigger control or unstable shooting positions. While technique is important, improper application of the shooting fundamentals can be overcome with proper training and practice. The three worst habits are attitudinal, and they can rear their ugly heads even after you learn the proper technique. These three worst habits are:

- Focusing too much on the minutia

- Focusing too much on the target

- Focusing too much on misses

Focusing on the minutia

When a shooter is too focused on the minutia of long-range shooting they often forget their fundamentals. The shooter stresses about variables that will have a minor effect on their accuracy — and ends up jerking the trigger.

Well, you caught me. I just said that the three bad habits of unsuccessful long-range shooters don’t involve the proper application of the fundamentals. I just wrote that the #1 bad habit involves skipping the proper application of shooting fundamentals. Let me explain . . .

The problem isn’t jerking the trigger per se. It’s worrying about the spin of the Earth — instead of focusing on proper trigger control. It’s worrying about how level the rifle is — instead of remembering how to breathe. It’s calculating the humidity effect on the bullet’s path — instead of adjusting the scope’s elevation turret for the appropriate distance.

Long range shooting can be difficult. There’s a lot to learn and master. But it’s not that complicated. Accurate long-range shooting can be broken down to two main tasks: pointing the rifle in the proper direction and firing the rifle without disturbing its alignment. Getting the rifle pointed in the exact right orientation is irrelevant if you’re going to change its position by yanking the trigger.

If you want to progress, you need to focus on these basics first and move on to the advanced parts later. If you can’t shoot at least a 1” group at 100 yards consistently, it’s not time to consider the Coriolis effect. If you aren’t able to shoot your rifle without jerking the trigger, you shouldn’t be trying to shoot from advanced positions.

Focusing on the target

A lot of long-range shooters fall in love with the target. That’s because their high-end scopes present a nice clear image of the target; they want nothing in this world more than to put the neat little holes in the middle. So shooters tend to stare at it.

Magnification is not your friend. With a clear, sharp image of the target in a scope, it’s all too easy to look past the reticle and focus on the target. This can cause the reticle to drift out of proper alignment with the target without the shooter noticing.

When I walk up and down the firing line of sniper students I constantly repeat a simple mantra: “focus on the reticle, steady pressure on the trigger.” Whatever the actual reason for their miss, it’s often resolved by focusing on what you can control instead of what you can’t.

One of the fundamentals to accurately shooting with iron sights is focusing on the front sight. Focusing on the reticle of a rifle scope is just as important. You can often correct the bad habit of target fixation just by turning down the magnification on your scope or shooting a bit with iron sights.

Focusing on misses

If you’re a long-range shooter you’re going to miss the target. Or the center of the target. When you focus too much on a missed shot, you increase the chances of missing the following shot. You can hear unsuccessful shooters discussing and analyzing their missed shot instead of discussing what they need to do to make a hit.

Spotter: Oooh, that was a little low.

Shooter: How low?

Spotter: Umm, about a foot. Did you jerk it?

Shooter: I don’ t think so. This ammo sucks/the temperature calculation is wrong/my iPhone application gave me the wrong data/etc.

That’s not to say you should ignore a missed shot. You can learn a lot about why you missed that you can use to get a hit. But once you’ve analyzed an error, even if you’re not entirely sure exactly what you did wrong, don’t focus on it. Change what you need to change and make the next shot better.

Keep it short and simple. After shooting, call your shot and reload your rifle. All that chatter about the direction of the miss, the reason for the miss and the [possible] correction required takes up valuable time. And time is not your friend, either. One example: wind.

Wind is the most difficult variable when shooting long-range. The best time to shoot is immediately after you’ve seen exactly what the wind did to your bullet. If you wait too long, the wind may change and you’ll be back to square one.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve seen too much attention paid to a missed shot by a shooter who then forgot to reload their rifle. By the time they were ready to shoot again, they made the worst kind of miss possible: the bullet didn’t even get closer to the target because the gun didn’t fire.

Conclusion

When I was taking the U.S. Military’s Special Operations Target Interdiction Course (SOTIC), I learned to accept an inarguable fact: the previous round was down-range. There was nothing I could do to bring it back or change the miss into a hit. I learned to let it go. To go back to basics and focus all my attention on getting them right. To make the next shot count. It’s a lesson that’s helped me both on and off the range.

——–

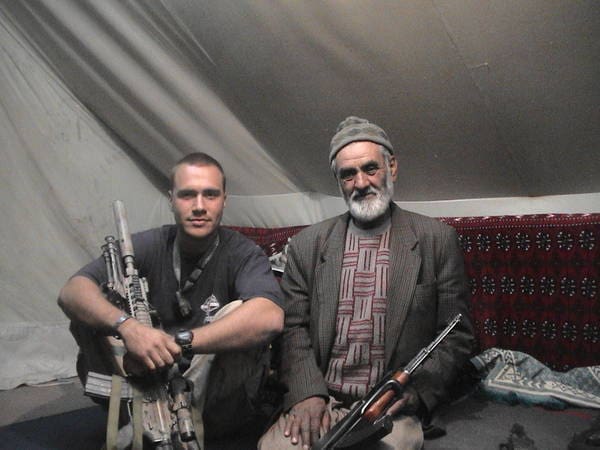

Ryan Cleckner was a special operations sniper team leader in the US Army’s 1st Ranger Bn (75th) with multiple combat deployments and a sniper instructor. He has a series of basic online instructional videos (more to come shortly) and his book, Long Range Shooting Handbook, is available for pre-order at Amazon.

Also it’s supposed to be FUN. We shoot clays proped on a berm @ 200 meters. Using two shooters one starting on the left and one on the right. Fast as you can reload and nail em’ or a 10 shot challenge. It’s pretty amazing what you can do with a Mosin and surplus ammo. Fun,Fun,Fun.

Love Fun. Fun has pretty much been beaten out of the masses these days.

Blame the “fanboys”. Those that are so into the whole thing that anyone who can’t do as well as them, know as much as them, or have all the same stuff as them, are derided until they give up. The fanboys (of whatever you are talking about, shooting, cars, video games, whatever) want to make a small pond even smaller so they can be very big fish indeed. They’ll ruin anything, shooting included.

Nothing gave me greater pleasure than beating “Damn I’m Good” Dave. He was one of those people you are talking about. He finally had to find another pond to swim in

Exactly right…

“Fun has pretty much been beaten out of the masses these days.”

I can introduce you to an ex of mine, Sal.

She was kinda into that kinda ‘thing’.

DEVO wrote a song about her…

(Ouch! The memories… 🙂 )

Thanks Geoff but I’ll pass

“Working in a Coalmine”?

Over thinking it, I’ve found that is the worst habit for consistent accuracy..and yanking the trigger.

The first thing people do wrong is not finding a mentor to teach them. The second thing they do is not listen to that mentor. The last thing they do wrong is focus on the target/minutia/misses.

If you want to be successful let me save you thousands of dollars: Get a mentor, listen to him/her and then read this article again and understand that what it says is: You’re not perfect, you’re fallible. Accept that you can fail and try hard not to.

Indeed.

Your post showed the most wisdom in the advice you gave about finding a “teacher”. Shooting, especially shooting, trying to reverse bad/inefficient habits is most difficult.

I can teach my 14 yr old Son in one day how to shoot to 500 meters and the fundamentals that led up to the hit. Now trying to “teach” an “experienced” Shooter to hit the same target.. days

Everything in this article is true. Years ago I could place 18 rounds out of 20 on a basketball size target at 600 yards with open sights using a M16A2. Doubtful I could do that today. The ONLY reason I could do that is accepting instruction and applying it. That instruction included dry firing on barrels mid afternoon in 100 degree heat or a range instructor placing his boot on my junk to slow my rate of fire.

All done before the age of red dots, scopes, and the only ballistic computer was a note pad, no.2 pencil and your melon.

Was that boot applied with a swift, vicious kick?

(Sorry, had to do it, man… 🙂 )

No just slow steady pressure…cures that trigger jerk real quick.

Ah yes, good times. I still try to practice the methods taught during my time at Ft. Benning. My biggest hurdle has always been trigger-squeeze, so I often spend a bit of time balancing a dime on the barrel. And to this day I still shoot better with irons out to 300m than with optics.

Over time, when principles of shooting becomes your nature, a firing line becomes a chapel. Accepting the physical, and ease into metal aspects of the craft. The body becomes sensors pulling in the moment…data yours to shape into a sucessful squeeze, bullet knows upon leaving it’s done. North east in black…held respiratory pause few milliseconds longer than required. Noted…to the alter again where absolution seeks perfection placing holes in paper.

From personal experience my enemy is anticipation of recoil. That would fall under over thinking it. I really love when it happens right, which is thankfully a lot more than not. 1/4 inch groups at 100 yards are not as consistent as I would like but I am getting better. Applying principles from other sports like focus and adjusting for errors without dwelling on them helps a lot.

You’re certainly not the only person who has wrestled with the noise/recoil-anticipation monster. Every one of us has SOME level of deep-seated fear of loud explosive-type noises right close to our faces (sometimes matched by the dancing FIRE (!) of muzzle flash), accompanied by a sometimes-gentle, sometimes-not “thump” on the shoulder or palm. These fears and physical reactions to same are buried deep in our prehistoric animal hindbrain, and it’s a true challenge to get the “modern” part of modern man (and woman) to ignore these ancient impulses.

It’s also MUCH easier to PREVENT anticipation problems, than it is to get rid of them, once they are ingrained. Start with smaller calibers, moving up only when you have proven to yourself that you can control the instinctive reaction to the caliber you are currently shooting. Don’t shoot so much that you get tired and sloppy; that makes bad habits easier to pick up. Just because you brought 200 rounds of .44 ammo to the range, doesn’t mean you have to shoot all 200 before leaving; they won’t “go bad” before your next trip. Know your limits; if the .30-06 is all you can comfortably handle without twitching, then don’t tackle the .490 Louden-Boomer your buddy just bought, just because he thinks you should. Instead, take pleasure in watching HIM scatter shots all over the paper, even with his .22 when he’s done shooting the big gun.

And please DON’T be that guy that thinks it’s funny to hand the new shooter a 5-pound 12-gauge loaded with 3″ buckshot, or a snubbie revolver with magnum loads; the long-term damage of recoil anticipation you might do to a potential new shooter is NOT worth your temporary mirth and adolescent giggles/laughs.

Well said about the joke with recoil

Well said!! My wife’s ex was juvenile after she out shot him with his .44. Had her hold a 94 Win. Away from her shoulder and shoot. Needless to say it that likely contributed to his ex status.

It took about a year to get her to shoot a long gun, now she shoots most anything.

The point being, fear of recoil can be overcome. It’s based on trust, training and basics.

Bottom line, have fun!

Tom, that new Ruger Precision Rifle you bought (in .308 if memory serves) was turning in groups rather worse than the same rifle TTAG tested, that rifle in 6.5 Creedmoor was +- 1 MOA.

Have you had a chance to work up some handloads to see what what it should be capable of?

The reason I’m asking is that Dyspeptic was quoting below a ballpark price of 2K for the rifle alone, and the Ruger sells their’s for about $1300.

$700 in savings is nothing to sneeze at, that’s a nice down-payment on a decent scope right there…

Great article! Thank you.

And too many shooters start shooting with a semi-auto rifle. They get into a mindset of “Oh, I’ll just immediately correct and send another round downrange…”

+1

Nothing better than a bolt action rifle to train yourself in mindful, and accurate, shooting.

Over analyzing the miss is a big one. If you miss low left very often the next shot is going to be high right. Unless you know exactly why you missed, it’s sort of like golf. I have a wicked slice, but every time I try and compensate by aiming left I end up driving the ball straight into the woods on the left of the fairway. Unless you know the miss was something simple like a blown wind call or a blow n range estimation, aiming to the opposite side of where you miss was will likely just result in you sending a bullet to the new point of aim.

I’m not a long range shooter by any stretch of the word, but unless you are shooting well past 1000yds at really small targets, focusing on minutia like spin drift, Coriolis, etc is just going to result in a lot of time f*king with your telephone/ ballistics calculator while the guy next to you is busy scoring hits.

You’re right. I’ve made paper targets that make it difficult for a shooter to see where their impact is at 100 yards. Essentially, I used a camo pattern of circles in various shades of grey and black. This way, they can’t see which direction they missed and I’ll refuse to tell them until they are done shooting their group.

I could google this but am feeling lazy… dare these targets for sale anywhere? I have had more than one amazing group ruined by that feeling you get when I am on a roll and look through the scope and see the first 3-4 rounds are touching and then yank the last one because I got too excited.

There’s a link in my new book (link for book in bio at bottom of article above) that allows you to download all of my custom targets. Included are targets that help you zero your rifle too with MOA adjustments printed right on the paper for different zero distances (25, 50, 75, 100, 200).

Best book ever for shooting.

The Inner Game of Tennis.

Hint- it’s not about tennis.

It’s about quieting the inner mind and moving on to success and forgetting the last failure.

Never forget the importance of missing. It just means you get to shoot more. Also, walking your rounds into the target is a hell of a lot of fun too.

I totally blew an easy shot on a pig a couple of weeks ago. I can tell you exactly where the pig was when I pulled the trigger…I have no idea where my reticle was at that time.

Focusing too much on the target, and the existence of wind, are my biggest challenges in shooting.

Perfect example! This is the hardest thing for me to change when shooting a sporting shotgun. Whenever I stare at my shotgun’s bead and not the clay pigeon (or real bird), I miss.

More articles like this please. Handgun shooting and self-defense shooting have been covered ad nauseum on this site. Some instructional articles on other types of shooting would be nice.

I hate these “how not to do it” articles because then I will start thinking about it. Good thing my short term memory is shot.

Another thing I see today: Too many shooters don’t know the fundamentals, starting with “natural point of aim.”

If you’re shooting from any position, there’s a point where you and the rifle are going to be pointed when you relax your body. If you unload the rifle, take a sight picture, then close your eyes and relax, then you open your eyes again and look at where you’re aiming – that’s your natural point of aim.

When I’m shooting prone, I will spend a couple of minutes getting into a comfortable position in my jacket, with my sling all snugged up, and the rifle on my shoulder. Then I’ll relax, close my eyes and see where the rifle is aimed when I re-open my eyes. I’ll then wiggle and squirm on the mat until I can get the relaxed point to be on target.

What’s the point of all this adjustment and wriggling around? When you’re on target and relaxed, guess what? It takes very little energy from you to remain on target. If you’re having to contort yourself in order to put the rifle on target, sooner or later you’ll become fatigued (even if you won’t admit it) and your fine motor control starts to suffer.

” Too many shooters don’t know the fundamentals, starting with “natural point of aim.””

This. Oh, 1000x this. Please repeat this loud and often.

This is one thing I go over and over with my children.

I find it very instructive to watch KJW videos. She often (if not always) closes her eyes as she shoulders her rifle, and, there’s a reason for that.

The less you have to “compensate” your body position, the fewer variables you have to contend with.

Oh man…natural point of aim is big one on the list of fundamentals.

DG is spot on. Take out twisted or loaded muscles MOA gets smaller. I cannot count the times I stood behind a firing line and watched upper body twist to come on target. Or seasoned shooters bang Ables only to shank a Charlie…why…lifted a heel. Or while just before releasing an arrow squeezing the bow.

Controlling your body places the shot.

I tend to agree with all three points, particularly the first. I can, and have, taken a brand new rifle shooter out and sat them behind one of my precision rifles, did the calcs, dialed in the scope, and then told them to hold on the center and gently press the trigger until the gun goes off. Sure enough, they hit the target, time and again, at ranges out to 400-500 yards. Their minds are unencumbered by all the other stuff, and all they needed to concentrate on was pressing the trigger while holding point of aim.

As Nobutada explained to Captain Algren in The Last Samurai, “Too many mind….”

“Focusing on misses”

Agree 100%.

One must let go of “ego” to get better at shooting in general, and long range in particular.

It helps a LOT to have a spotter that understands what you are doing and is not injecting “ego” into his/her calls.

If you are not missing some while training/practicing, whether on the static pistol range or long range rifle, you are not challenging yourself. Therefore, misses are positives in that’s where we learn.

My longest hit (steel target) was less about any “skill” I had and much more about the coaching my (very accomplished long range shooter) spotter was giving me. Been shooting with that dude over 20 years, and still learn a lot from him….

Great article. I know that I’ve focused too much on the target, and I’ve definitely screwed up wind calculation. Long range accuracy is a long chain with many weak links. I’ve always admired the people who do it well, as well as their positive mindset.

Like Mk10108, my intro to long range shooting was the USMC known distance range shooting M855 from an M16A2 at 500 yards with peep sights. Thankfully I shot with the morning crew and typically had light winds. I was amazed that those M16’s with all those rattles could shoot about 2 MOA if the man behind the trigger did his part.

Here is what I want to know: when I shoot a 2″ group at 100 yards on a really nice concrete bench rest (complete with sand bags to hold the rifle perfectly), how do I know what is causing the relatively large group?

— Is it me?

— Is it my $250 rifle manufactured in 2012?

— Is it my $200 scope (3-9X) manufactured in 2012?

— Is it inexpensive ammunition?

(Inexpensive ammunition means $20 per box of 20 cartridges … for recently manufactured Winchester, Remington, or Federal ammunition.)

Looking at it another way, assuming that my shooting technique is absolutely perfect, just how much money do I have to spend on a rifle, scope, scope mounts, and ammunition to get 1/2 MOA accuracy?

It depends. What are you starting with? What cartridge, what action, etc, etc?

Generally speaking, to get to a true 1/2 MOA rifle (ie, not just 3-round groups, but 5 and 10 round groups under 1/2 MOA), you’re looking at spending $2K on the rifle and up. You’re going to have to hand load or settle on a cartridge where you can buy actual “match grade” ammunition (ie, .223, .308, etc).

Scope prices are on top of the rifle and ammo. You can pull a 1/2 MOA group from a rifle just by clamping the rifle to a rest and then shooting to whereever the rifle is pointing.

Thank you Dyseptic.

I shoot .243 Winchester out of a Handi-Rifle (break action single-shot of course) as well as .270 Winchester out of an inexpensive bolt-action rifle with a synthetic stock.

I figure the .243 Handi-Rifle should inherently be pretty darned accurate since it is a break-action rifle with what is effectively a bull-barrel. And its trigger is excellent: about 4 pounds break with no take-up, creep, or grit … and then a surprise break.

As for the .270 bolt-action rifle, its synthetic stock should not change due to temperature nor humidity. And I verified that the barrel is free-floating. So, at least it has those attributes going for it.

Given that I am shooting generic, inexpensive ammunition and using inexpensive scopes, 2.5 inch groups at 100 yards sound like they might about what I should expect. That is somewhat surprising to me since I shoot 2.5 inch groups at 30 yards with compound bow … using a peep sight on the string and a pin in front while holding 18 pounds on the string!

The .270 Winchester has suffered for many years from a lack of premium target bullets. It has always been a “hunting” round, and as such it wasn’t until recently that all-copper bullets of match grade were available.

I put a Barnes TSX 150gr bullet over my standard 150gr load in a .270 Winchester, on a post-64 Model 70 with the factory 22″ barrel, and I watched the groups close up from about 2″+ to about 0.75″ – just by changing the bullet and seating depth. Nothing else done to the rifle other than a trigger job.

A break-action rifle can be very accurate, but again, you’ll need to do some load development. I keep stressing this point over and over, and people who have never reloaded seriously don’t understand how much difference a change in load can make for accuracy. People who want to load for accuracy should get a Lyman reloading book, because Lyman calls out not only the maximum and starting loads, but for many cartridges they also call out an accuracy load. In almost no case is the accuracy load the maximum load for that cartridge.

When loading your own, you get to choose a bullet (which can make a big difference), your brass, your primer, your powder, your seating depth and whether or not you resize your brass to minimum sizes. Too many people today don’t understand how many variables there are in reloading and how it affects your accuracy.

Almost no one that I’ve read of, and no one of my personal acquaintance, who shoots in accuracy pursuits (benchrest, Palma, DCM matches or F-class) shoots factory ammo. Everyone I know (including me) who shoots for accuracy in any centerfire cartridge reloads. The only factory ammo I buy for accuracy is rimfire, and my rimfire match ammo costs be $0.13 to $0.20/round.

Thank you Dyseptic.

I’ll have to wait a few more years before I can justify the time and expense of precision long-range shooting. For now, I’ll take solace in “good enough” for my current big-game hunting scenarios as I just mentioned to Accur81 below.

I agree with DG, but I think it’s realistic to start on the cheapest part of the accuracy chain: ammunition. Start with Eagle Eye or Federal Gold Metal Match and a clean gun.

A lot of initial precision marksmanship classes break down the process. You’ll start with a detail rifle clean with a bore guide. Off comes the scope, and it gets re-mounted with appropriate tightness to all screws after the gun and reticle are leveled. Load up premium ammo, set your parallax adjustment, and start making adjustments to the scope as needed.

The old .223 and .308 from quality bolt guns and Leupold Mark IV scopes and Federal GMM are good starting points.

Accur81,

All good tips. I did make absolutely certain that all of my scope mount screws are tight so that I don’t have to worry about that.

I wonder how much of my group size is ammunition, how much is the barrel, and how much is due to variability in my cheek weld — and hence slight variations in my actual point of aim between shots.

Oh, and wind. I am nearly certain that I have never sighted in on a calm day. There is always at least a slight breeze (7 mph) blowing and swirling.

The other thing I always question is reticle size. At 100 yards, my reticle appears to cover an area of about 1.5 inches on the target. Whatever it is, it seems like I experience a fair amount of uncertainty about whether the center of the reticle really covers the center of the target … as it seems like my point of aim could easily be off by 1/2 inch and not realize it.

Reticle size and magnification definitely affect group size. Given a decent scope, a 12x, 15x, or 18x scope will give you greater target resolution and accuracy potential. My Burris XTR 312 only tops out at 12x, whereas my Bushnell ERS tops out at 21x. My Redfield 3-9x on my Win 70 .30-06 is a simple duplex design, making it more difficult to see 1/2 – 1″ bullseyes at 100, 200, or 300 yards.

That and I think there are a lot of folks who are unrealistically optimistic about the group sizes they are actually shooting.

That and I think there are a lot of folks who are unrealistically optimistic about the group sizes they are actually shooting.

Truer words are quite rare in the shooting industry.

Accur81,

In order to try and compensate for my large-ish reticle size, I have started a new technique where I try to, let’s call it “center” the horizontal and verticle reticles on the thick horizontal and vertical lines on my target … or I try to center them on the circle on my target (visualize trying to make four exactly even pieces of pie on that circle).

While those techniques might help, it tells me that I just don’t have enough magnification since all of my scopes max at 9X … which is great for rapid target acquisition and deer hunting out to 200 yards and lack luster beyond that.

Since my primary activity is deer hunting out to 200 yards, my 2.5 inch group at 100 yards should be 5 inches at 200 yards … which should be good enough if I do my part. So far, I have put shots exactly where I wanted on deer between 100 and 150 yards. I suppose I will take solace in that … and relegate true precision long-range shooting for another time when I can afford a better scope and match-grade ammunition (or the expense required to acquire hand-loading equipment).

1st rule and last rule: minimize human contact with the rifle.

Amen.

Forgive me if I’m wrong but if you crosshairs and your target are not on the same focal plane doesn’t that mean you have failed to adjust your scope properly?

Yes. However, sometimes (see good example above in comments re: pig hunting) a shooter will shift their focus to the target and let the reticle drift away from where it should be because they aren’t paying attention to it. When I talk about looking “past/beyond” the reticle, I don’t mean that they aren’t on the same plane.

I see. Thanks.

B – breathe

R – relax

A – aim

S – slack (trigger take up)

S – squeeze

Seems trivial, but works well for me whether it’s short or long range. Negates the 3 bad habits for most. If you apply BRASS consistently, there won’t be many misses to focus on in the first place.

Ryan

Here are some free printable to-scale targets (MOA and MIL), feel free to use and share. They have had almost 100,000 downloads so far.

http://www.stormtactical.com/stu.htm

Comments are closed.