Arriving in Roswell, New Mexico, I got hip to our mission. Ritter & Stark wanted to push the limits of what a production rifle can do with production ammunition, all while providing a few gun writers some trigger time behind their upcoming SLX short action rifle. How far is “pushing the limits” of a factory rifle? Will 4,000 yards (2.27 miles) do the trick?

Attempting to achieve hits at that range was Ritter & Stark’s SX-1 MTR rifle (reviewed on TTAG here) set up for .338 Lapua Magnum. We were using off-the-shelf ammo from Nosler and Prime.

ELR — extreme long range — shooting requires holding for more elevation than any scope can dial in. One way to deal with this is through the use of a heavily-canted scope mount. Various options exist, most of which are adjustable so only the amount of additional angle needed has to be dialed in. Limiting that cant is desired since it raises the rear of the scope and can make getting a normal cheek weld difficult.

Believe it or not, yes, you can still see through the scope even though it’s looking straight at the barrel. Since it’s focused way off into the distance, it “sees” around those close objects, gathering and collimating the light back into a coherent image. It’s just a bit darker than usual depending on how much light is being blocked by the barrel and such.

Another option, and arguably a much better (though more expensive) one, is the TacomHQ Charlie TARAC. It’s an adjustable mirror device that clamps either onto the objective bell of the scope or onto the Picatinny rail in front of it.

Adjusting via a couple of gears on the right side, the Charlie can provide up to 412 minutes of additional elevation. Combined with the scope’s internal adjustment, this will get you way the hell out there while allowing for a level scope mounted at a normal height. Price? About $1,420.

You’re gonna need that elevation, too. 4,000 yards is way the heck out there. It’s 2.273 miles. It requires 317 minutes of elevation according to a ballistics app, but even more in practice (more on that later). Even if you were lucky enough to have a scope/rifle setup that zeroed out at the bottom of the scope’s adjustment range, these distances are going to require at least three times more elevation hold than the scope is capable of.

This is so far that a .338 LM projectile is going to apex at about 1,325 feet above the shooter while it’s rainbowing out to the 40×40″ steel target we were shooting at. Flight time is a blink short of 10 seconds. You may be good at reading the wind between you and the target, but when the bullet spends most of its time many hundreds of feet above you, you’re simply guessing.

Worse yet, as a projectile goes transonic — moves from supersonic to subsonic — it typically loses stability. Depending on the bullet’s length, mass, shape, spin rate, and other factors, it may simply wobble before re-stabilizing or it may go completely off the rails. When you go beyond transonic, you lose predictability.

In our case, factory ammunition was not up to the task of hitting a 4,000-yard target without time and luck. Though both Nosler and Prime are quality manufacturers (Prime being manufactured by RUAG, Swiss-based makers of Norma and other high-end brands) producing a consistent product, it isn’t consistent enough. Even small velocity deviations at the muzzle are huge point of impact deviations a couple miles downrange.

I only took five shots at the 4k target and didn’t hit, though I was all around the darn thing missing by relatively small amounts (it was white as a ghost; clearly scared). Seen above is a target that I did hit at 2,600 yards (1.48 miles). At this range, the bullets were already tumbling. Three out of four impacts on the plate hit sideways or close to it.

Even at 2,600 yards, making consistent hits was really beyond the abilities of the ammo even if there was no velocity deviation. While the SX-1 has put up quarter-minute groups with these loads, it simply doesn’t matter. Once those bullets begin tumbling, which probably happened during or shortly after they went transonic at about 1,900 yards, all bets are off. That loss of ballistic coefficient due to long, skinny bullets becoming wide, sideways bullets explains the need for about 365 minutes of actual elevation adjustment instead of the calculated 317.

Ultimately, shot-to-shot chasing of wind holds or vertical drop variances was an exercise in futility. “One minute off the left side” doesn’t mean you pulled your shot or misread the wind. Not necessarily. So holding a minute to the right on the next shot is probably a mistake. With tumbling, unstable bullets, even completely flawless, dead-center-held shots in still conditions with the most accurate rifle in the world will leave you begging for better luck. And precision rifle shooting shouldn’t be about luck.

That doesn’t mean it isn’t a ton of fun, though. Lobbing bullets out to distances measured in miles and coming really close is about as addictive as anything can be. Get a few people on spotting scopes to exclaim “OOooooohh!!!! JUST off the left edge!!” and try to walk away from the rifle with that as your last shot. Big boy ammo isn’t cheap, but in an environment like this you’re going to max out your credit card before quitting without a hit.

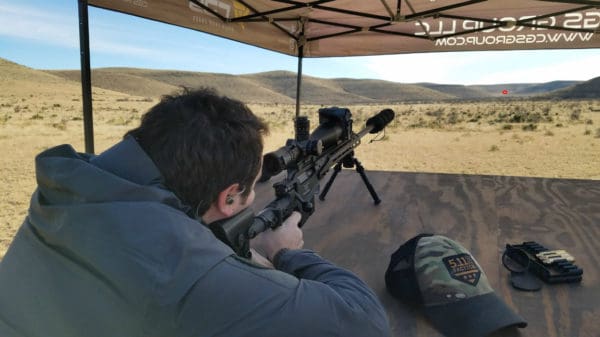

I also got some time behind CruxOrd’s new tripod systems. Shooting the SLX in .308 off the tripod both standing and seated, I made consistent hits on steel out to about 1,300 yards and bracketed an IPSC silhouette at 1,960. Yes, we were lobbing .308s out past a mile with shockingly good results, seeing misses splash in the dirt all around the target and within inches of it, though I can’t confirm if contact was ever made.

From seated, shooting the SX-1 MTR in .338 LM, one of the shooters hit at 2,600 yards. Pretty sweet, really, from a portable tripod setup that allows full X,Y,Z articulation of the rifle with extraordinarily smooth motion. Great for hunting or that “overwatch” sniper role.

At the 4,000 yard target, the .338 bullets were only doing around 800 fps. They had maybe 975 fps left in ’em at 2,600 yards. This combined with the downwards angle as they dropped out of the sky made recovering projectiles relatively simple. Most were exactly where we saw them impact through the spotting scopes, hits were sitting right at the base of the target, and others were visible reflecting the sunlight as they sat on top of the ground. Seen above is a bullet that clipped the edge of the target. Awesome.

Overall, my time outside of Roswell was both fun and educational. Even if I didn’t make hits at that astonishingly far 4,000 yard distance — you could see the target just fine with the naked eye, by the way — I did set a new personal record of 2,600. I saw with my own eyes how much impact deviation there is due to ammo velocity deviations from five to 40 fps.

I put a few hundred rounds through Ritter & Stark’s upcoming SLX rifle, too, and will follow up with another article just on the SLX.

I learned that ELR shooting involves a lot of unique considerations and equipment. Whether it’s specialized optical gear to enable sufficient elevation holds, an accurate rifle on a stable rest, extremely consistent ammo, Tomcars to get down to the target and back, or nice enough spotting scopes to call hits and misses (in particular one with a reticle so misses can be measured in MOA or Mils from the target), there are many necessary components. And any one of them can be the difference between success and failure.

I think it would be fun to try, regardless, and it only forces the market to push the envelope as well (I want in as both a shooter and a loader).

What is the practical application otherwise? Someday we’ll need a drone to go around the 25 mile curvature of the earth to direct hits?

Check out the Mark and Sam After Work YouTube channel. In addition to the 1 – 3 thousand-plus yard shots, they’re now working on getting consistent 5K hits. And their target is smaller. Regardless, fascinating to see just what goes into trying to make such shots.

I’ve been following them for about a year. Incredible shots they make.

That looks fun, but it’s so difficult to find a place to shoot more than a few hundred yards. And the ammo is expensive and time consuming to hand load. My precision .308 it about a dollar per shot, and can group about an inch at the longest range I have access to (600 yards).

That’s why I’m going the opposite direction. Next week I’m assembling a 10/22 from precision parts (mostly Kidd, only the magazine will be Ruger) for a local PRS style .22 league.

try finding anywhere you can shoot more than 1000 yards here in australia…… imf^&%$@gpossible. most you can shoot at 98% of places in australia is 500 yards.

Interesting pic of the bullet that edged the target. It appears the shear occurred at a twist faster than the engraving on the bullet. I’ve always wondered at what rate bullets lose spin rate. At least in this case it appears velocity was dropping faster than spin. Then again, if this occurred beyond the transonic region, who knows?

Spin barely slows during a bullet’s flight. This bullet left the barrel at 181,637 rpm and a few seconds of floating in the air doesn’t knock much of that off.

That sounds like a really fun time. It also explains why none of my bullets have hit the ” we were here” marker on the moon.

Way too cool Jeremy.

I love distance shooting.

Comments are closed.