By Ryan Cleckner

If you don’t take the right precautions, you can experience galling when you are connecting two pieces of stainless steel, aluminum, or titanium (and some other metals). Galling is the wearing away of the surface of certain materials that can lead to parts being permanently stuck together (friction/cold-welded).

For example, attaching a titanium muzzle brake to a stainless steel barrel or that same barrel into a stainless steel receiver can result in a permanent fusion of the two pieces. The term galling is also used for something that’s annoying. As you can imagine, both definitions surely apply here.

When it comes to working with certain metals — stainless steel, aluminum, and titanium are the most common with firearms — you need to add a protective layer between the two surfaces you’re joining to prevent this kind of friction/cold-welding. If you read instructions that come with some of these parts (I rarely do), you might notice that manufacturers recommend using an “anti-seize” lubricant during installation. This isn’t just to make the parts easier to install, it’s a necessary step to prevent the permanently fusing the parts.

These metals have a naturally occurring layer of oxide which protects themfrom corrosion. This is one of the reasons why these materials are so widely used in firearms. However, under the friction of being rubbed against each other (like threads screwing into each other), the thin layer of protective oxide can be worn-away exposing the raw metal itself. When these unprotected/raw surfaces come into contact with each other, adhesion (sticking together) can result. This is bad! The adhesion can be so strong that you’ll break the parts when trying to disassemble them or you won’t get them apart at all.

To avoid this problem, you can either use different materials or you can add your own protective layer that doesn’t wear away like the naturally occurring oxide layer does. For example, I’m a fan of stainless steel barrels. I like the corrosion resistance and the longevity that the harder material allows. However, when it comes to receivers, I’m partial to normal carbon steel.

There are two reasons for this. First, I like how the softer carbon steel “wears-in” and gets smoother faster and easier than a similar stainless steel action. Second, by using different materials I don’t need to worry about the metals galling (and I also avoid the feeling of how galling it can be to have stuck parts).

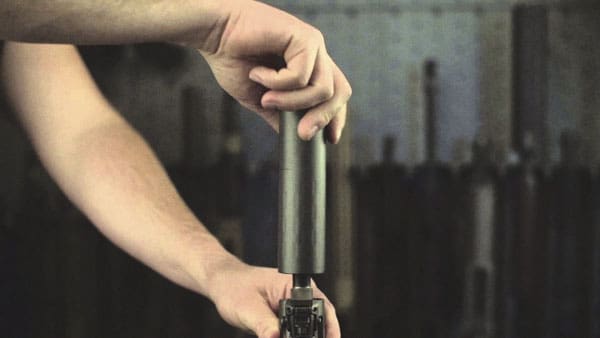

If you want to use these metals in contact with each other, then you must use anti-seize lubricant. A normal lubricant is better than nothing but anti-seize lubricant has properties that allow it to last longer and protect better. You can find anti-seize grease at your local auto parts store – a small amount will last you a lifetime of home-gunsmithing. Liberally apply the anti-seize lubricant to the threads, attach the parts to the proper torque specification, and then wipe away any excess lubricant. It’s that simple.

Knowing about and preventing galling will save you costly trips to a gunsmith and it will allow you to maintain and upgrade your products later. To many, a barrel will last a lifetime. However, I believe that a barrel on a rifle is like a set of tires on a car – eventually they’ll need to be replaced. Use the correct metals or use anti-seize lubricant to prevent a galling experience!

Ryan Cleckner is the author of the Long Range Shooting Handbook.

The most common use for anti seize in firearms, is the breech plug in a black powder gun, and the receiver to frame fit on a 1911. Also as far as I understand you can use small amounts of anti seize anywhere a lubricant goes, but not vice versa. That lube is it’s own animal.

Nice article.

these compounds contain metals and will act abrasively if used at a lubrication point that sustains load. not normally a grease substitute.

Abrasively even though the metal in the anti-seize is softer than than the metals joined, like copper anti-seize compound on two steel parts?

with high friction/ loading i would be concerned.

i was out of lithium grease so i anti- seized all of the nylon bushing pivot points on a snowmobile suspension. they never bound, but they wore abnormally quickly.

due to the fact that the anti- seize we always had would unavoidably start to turn everything in the world silver no matter how carefully you were applying it, i switched to bel ray assembly lube (gorrilla snot with a brush in the can lid) and haven’t looked back.

Loctite 51609…no metal, heavy duty, high pressure, anti-seize, lubricant.

…”Loctite lubricant”?

Oxymoron much?

*8)

Stainless steel bolts and nuts can seize together just spinning them down, before you even start torquing them down. Your only option then is to cut the bolt off and start over.

Have used anti-seize for decades on lots of metal to metal contact areas. Steel sparkplugs threaded into an aluminum head will seize solid if screwed into bare metal. I know how to get them out without wrecking the head (most of the time), buts it’s huge pain.

you never- seize to amaze me.

Bdump, tish!

Galvanic corrosion is the enemy, ti-prep or regular anti sieze will save a ton of trouble in the long run. Remember, you can use grease anywhere you would normally use anti sieze, but anti sieze makes a piss poor grease!

Depends upon the grease application.

In roller, ball or needle bearings, anti-seize (and even moly disulphide greases) are a poor way to go, because the suspended metal particles will close up the allowances between the balls/rollers/needles and the inner/outer races. The bearing might actually fail as a result. So you want pure greases, with no suspended metallic component in many of these applications.

In thread, sliding interface and other applications, now things become a bit more varied, and in some of these, anti-seize isn’t going to close up the gaps enough to cause problems.

All the above applies to fine mountain bikes as well. Lots of Al, steel and Ti mating points.

Bel Ray blue lid tub of moto grease EVERYWHERE ON ALL THE HARDWARE AND TOYS.

Lhstr, I use high pressure/temp. syn. Mobil grease on all my weapons, on slides and mating threads only. Oil the rest and all “Lightly”. Glocks like film only! To much lubricant is a dirt collector.

3m copper anti-seize, apply carefully or else you will be know as “the man with the golden gun” just like that old bond flick.

I learn something every day on this site. Good article.

A very good article here.

Everything Ryan says is true, in abundance. Further, the speed at which threaded joints between similar hardness stainless steels are screwed together has some bearing on how badly they might gall/weld together.

In things like the barrel/receiver joint, I use moly disulphide anti-seize/grease. In muzzle threads, I tend to use some copper-based anti-seize. Why the difference?

Moly grease/anti-seize is black. It will get everywhere. It’s a superior (IMO) anti-seize product, but it stains your clothes like nothing you’ve ever seen. So I put it where it is needed – where the barrel is torqued down into the receiver – at a rather high level of torque. Clean up the joint and you won’t see it again for (probably) at least 2K+ rounds. Odds of getting it all over you? Slim to none, unless you’re doing your own gunsmithing.

Muzzle brake/silencer threads? I used copper-based anti-seize. Odds that you, the gun owner, will have to deal with the lube getting on you? Pretty high. Level of torque applied to the threads? Nowhere nearly as much as for the barrel/receiver threads.

“Liberally apply the anti-seize lubricant to the threads, attach the parts to the proper torque specification, and then wipe away any excess lubricant.”

One important caution here. Threaded joints have (or should have) two different torque specifications: one for lubed joints and one for dry joints. Lubrication of a thread mechanism dramatically increases its efficiency at converting rotary torque into axial force, independent of the materials used. Torquing a lubed threaded joint to the specified dry joint torque value can often break the male fastener.

There is no hard and fast rule for how much to decrement the specified dry torque when torquing a lubed threaded fastener, but you should be able to find a torque chart which provides both torque values for most threaded fastener combinations.

If it’s worth spec’ing a torque on, the manufacturer has a chart, will spec wet or dry, and likely what general viscosity of lube if it’s wet.

One time I couldnt’ get a buffer tube off an AR for the life of me. Wound up drilling a hole through the tube and putting a screwdriver to torque it off in a vise. I wonder if the cold fusion thing is why that happened? Never had the problem before, and never had it since. So weird.

Heat is another factor. All steamfitters know about Never Seize or Anti Seize. We also used Copper Coat or a lead coat on flange studs, bolts and on gaskets. They work well in salt water areas also. always use some type of thread dressing on anything that is exposed or that gets hot, if you ever want to take it apart again.

Oh thank GOD, I was afraid you were going to say Crisco or Fireclean. / sarc !

Yes! Anti-seize, good stuff. you can get a bottle or little pouches of it up by the counter in most auto stores.

” Liberally apply the anti-seize lubricant to the threads, attach the parts to the proper torque specification, and then wipe away any excess lubricant. It’s that simple.” – although I wouldn’t put it (allow it to get on) anywhere the bullet is supposed to travel, and if you get it inside your can you’ll need ultrasonic cleaning to get it out.

Been using Permatex Anti-seize for decades. Permatex, is (petroleum) hydrotreated heavy naphthenic, aluminum powder and dewaxed paraffin oils.

On anything new, if a person had concerns, I would first insure any threads are very clean from any manufacturing machining and then use a little bit of anti-seize. No need to slop it on and make a big mess.

While the general ideas presented in the article are correct, many of the statements of fact are worded incorrectly.

It’s called dissimilar metal or galvanic corrosion. Oxides of whatever metal IS the corrosion. The four items you must have for corrosion are; Anode, Cathode, Electrolyte and a metalic pathway. The oils/grease/coatings work by seperating the electrolyte from the other 3. If always kept in a dry enviroment below 48% RH (relative humidity), there is then no electrolyte.

Check with a corrosion Engineer next time before you publish to make sure your statement of facts are worded correctly.

Class is over.

Comments are closed.