By Matthew D. Cubeiro

As directed by the California Legislature, the California Department of Justice, Bureau of Firearms (“CA DOJ”) recently released its 2020 report on the Armed and Prohibited Persons System (commonly known as “APPS”). For those unfamiliar with APPS, it is used by CA DOJ to cross-reference individuals who are prohibited from owning or possessing firearms, but may still be in possession of firearms.

California has been the only state to implement a program like APPS, raising the question why. The answer is simple—APPS is both ineffective and a waste of taxpayer resources.

Since its implementation, APPS has been plagued with problems, with many in the California Legislature questioning its effectiveness. The recent release of the 2020 report, in which CA DOJ clearly attempts to hide or otherwise distract from these problems, further serves to illustrate the program as a complete failure.

A Brief History of APPS

APPS was first created by SB 950 in 2001 and took effect in 2006. It was a direct response to an incident at Navistar’s International Truck and Engine Plant in Chicago where a twice-convicted felon used a firearm to kill four innocent co-workers before killing himself. According to SB 950’s author, APPS was intended to “provide a way for law enforcement to find out which proven felons are still possessing weapons” and provide law enforcement “with a tool that will disarm these proven law-breakers before they can break the law again.”[1]

But immediately following its implementation, problems began to emerge, particularly with funding and the growing backlog of individuals listed in APPS. This prompted the Legislature in 2013 to appropriate over $24 million from funds generated by lawful firearm transactions. In other words, law-abiding gun owners were stuck paying the bill for general law enforcement activities regarding firearms.[2]

Even so, that funding came with certain strings, including a required annual report to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee on DOJ’s progress reducing the backlog. Other items CA DOJ was mandated to report on include:

-

- The number of agents hired for enforcement of APPS

- The number of people cleared from APPS

- The number of people added to APPS

- The number of firearms recovered from enforcement of APPS

- Information regarding collaboration with local law enforcement on APPS

In 2018, CRPA published a detailed article concerning APPS and the various reports published by CA DOJ at the time. Notable is how over the years since the reporting requirement took effect, CA DOJ repeatedly changed its reporting methods, no doubt for purposes of casting APPS in the most favorable light possible. This makes it extremely difficult to effectively analyze the program’s effectiveness, both from a financial and public policy point of view.

Such problems have been compounded by the passage of SB 94 in 2019 which, among other provisions, re-establishes the reporting requirement and seeks more information regarding the terms CA DOJ used in its prior reports. Such terms include those individuals who are “unable to be located,” “unable to be cleared,” moved out-of-state, have federal prohibitions only, or are currently incarcerated.[3] What’s more, DOJ must also report on the degree to which the backlog in APPS has been reduced or eliminated.

CA DOJ’s Automated Firearms System

To be listed in APPS, an individual must both be prohibited from owning or possessing firearms and simultaneously have an entry in CA DOJ’s Automated Firearms System (“AFS”). AFS is the system used by California law enforcement to query prior Dealer Record of Sale (“DROS”) transaction history for a particular individual.

In most states, licensed firearm dealers conduct a background check on a prospective purchaser by submitting the purchaser’s information through an online federal system known as the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (“NICS”). But in California, licensed dealers instead send a purchaser’s information to CA DOJ, who in turn sends that same information to NICS while also checking additional state databases.

California licensed firearm dealers submit the required information using CA DOJ’s DROS Entry System (“DES”).[4] Assuming the prospective purchaser is deemed eligible and satisfies all other requirements, DROS information (which includes information about the firearm(s) being purchased) is then uploaded to AFS.

Many individuals—including California law enforcement—mistakenly view AFS as a registration system. A more accurate way of describing the system is a database containing firearm transaction records.

CA DOJ officials have testified to this fact repeatedly, stating instead that all an AFS record reflects is that on a particular date and time, the person applied to purchase or transfer a firearm and a background check was conducted in connection with that purchase or transfer. It does not indicate the person is in possession of the firearm.

Put bluntly, APPS relies on a database that doesn’t speak to a person’s possession of a firearm, and then uses that same system as a means of assuming the person is in possession of a firearm. It should therefore be no surprise why CA DOJ is often unable to clear persons listed in APPS.

What’s more, this says nothing about the accuracy of AFS entries themselves, many of which are problematic for reasons unrelated to the fact that they don’t speak to actual possession.[5]

The DOJ’s Twisted Definitions

Before analyzing the 2020 report, it is important to understand the terms used throughout. Many readers will likely overlook how those definitions are being used to manipulate the data to cast a favorable light on APPS. For example, DOJ defines the term “backlog” to mean:

The number of cases for which the Department did not initiate an investigation within six months of the case being added to APPS or a case for which the Department has not completed investigatory work within six months of initiating an investigation.

Previously, DOJ simply defined the term “backlog” to mean those cases in APPS that had not been fully investigated. The most recent statistic available for this figure was from 2018, with DOJ reporting approximately 8,373 individuals in APPS had not been fully investigated.

Following the change in the definition for the term “backlog,” however, DOJ now states that its systems do “not have the technological capability of tracking the amount of time a case has been in the system.” And as a result, DOJ is “unable to provide these statistics until upgrades are made to the APPS database.”

In other words, it is either too difficult now for DOJ to report this information, or worse, it doesn’t want to.

Other terms used throughout the report, such as “cleared,” “closed,” and “contacts” in relation to APPS case shed light on how the report misleads readers. A layman would think a “cleared” case is one where DOJ investigated the person and if found to be in possession of firearms confiscates them. But the definition as used by DOJ also includes cases where the individual died, their prohibition expired, or their prohibition was otherwise removed.

In other words, a “cleared” case also includes those cases for which DOJ likely did nothing at all.

Likewise, a layman would believe a “closed” case is that which has been fully completed. Instead, DOJ defines the term to be those cases where DOJ fully investigated the person, but their case remains “pending.” In other words, a “closed” case is one in which DOJ has simply given up on removing the person from APPS altogether.

But perhaps most blatant among such deceiving definitions is the term “contacts.” Undoubtedly, a layman would likely think the term to mean an actual contact between DOJ and an individual. Instead, DOJ defines the term as mere attempts to locate an APPS individual. Nowhere in DOJ’s is it clearly stated how many actual contacts DOJ made with person’s listed in APPS, physical or otherwise.

The DOJ’s Numbers Don’t Add Up

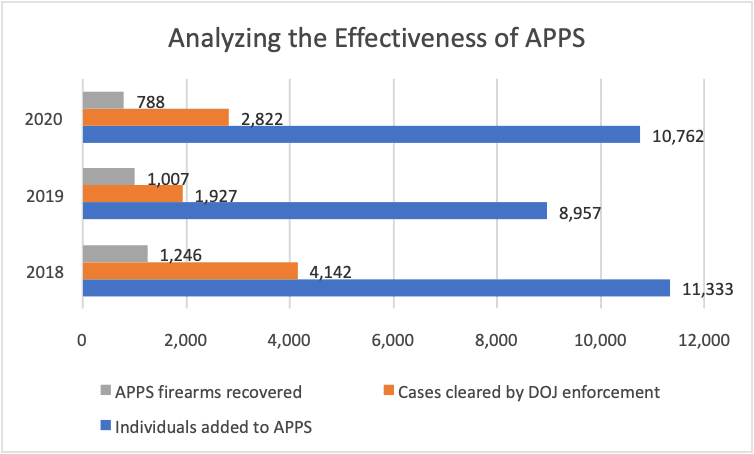

With a better understand of the terms used by CA DOJ, we can now look at the figures and statistics in the report and compare those to prior reporting periods. As a baseline to measure the effectiveness of the program, CA DOJ claims it “removed 8,370 prohibited persons from the APPS database” in 2020 while also noting that “10,762 prohibited persons were added to the APPS database” over the same time period. What is grossly misleading here is that CA DOJ is suggesting its actions are responsible for the removal of 8,370 prohibited persons from APPS.

Buried much deeper in the report is the actual number of individuals who CA DOJ were able to verify as being disassociated from their firearms. That number is only 2,822. The rest either died (257 individuals) or had their prohibitions expire (5,291 individuals).

In other words, nearly twice as many people were removed from APPS for reasons outside CA DOJ’s control. Which also means the number of individuals added to APPS in 2020 is about four times higher than the number of individuals CA DOJ was responsible for clearing.

A better comparison would be the number of firearms seized by CA DOJ agents. In 2020, DOJ claims to have recovered 788 firearms that were associated with an individual listed in APPS.[6]

What the report fails to address is how many of these firearms were associated with unique individuals. Many of the firearms seized were likely associated with the same person, as it is common for individuals who own firearms to have more than one.

Even if we are to assume every firearm seized was connected to a unique individual, this number suggests the number of individuals added to APPS each year outpaces those CA DOJ clears at a rate of nearly ten to one.

To be fair, CA DOJ also seized an additional 465 firearms in 2020 labeled as “non-APPS firearms,” meaning firearms which were not listed as being possessed by an APPS individual” but were nonetheless confiscated. We can at least be certain these firearms were seized during an APPS investigation.

What is not clear from the report, however, is the reason for their confiscation. Many of those firearms, for example, could have been confiscated from a spouse or roommate living with the prohibited person who is not actually listed in APPS.

That said, even if one were to account for the total number of firearms seized (1,243), that number is less than half of the total number of cases DOJ was able to clear from APPS due to their enforcement efforts. In other words, more than half of DOJ’s “successful” cases were the result of faulty or outdated information in AFS.

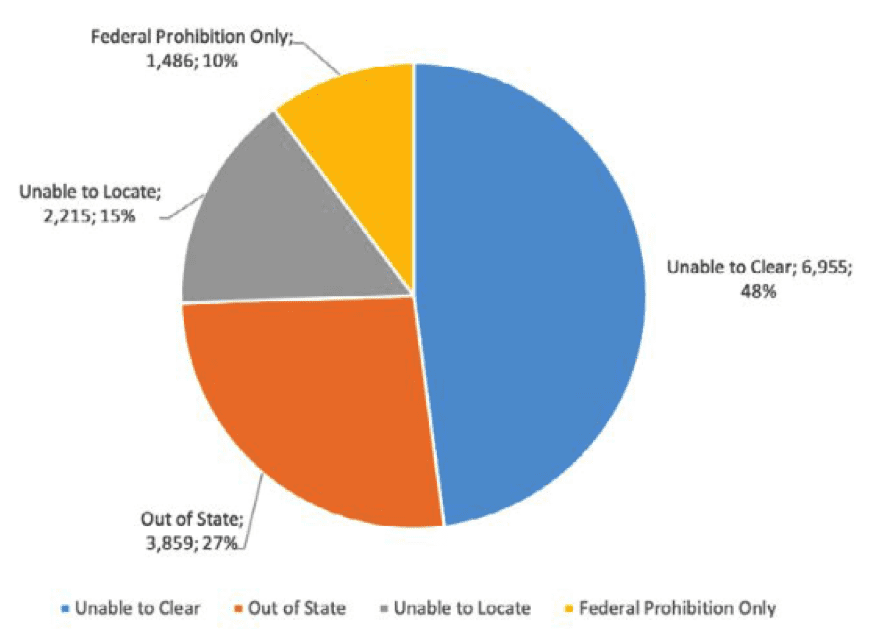

There is also the matter of the 14,515 individuals CA DOJ has placed into the “pending cases” category. The majority of these (6,955 individuals) consist of cases CA DOJ is “unable to clear” from APPS.

CA DOJ describes such cases as those that have “been investigated and all leads exhausted but agents have been unable to disassociate the individual from all known firearms.” In other words, “unable to clear” cases likely mean the individual has an AFS record that DOJ is unable to locate the associated firearm for. As noted above, this is not surprising given AFS does not reflect whether a person is in possession of the firearm.

The remaining cases consist of individuals who have since moved out of state, CA DOJ is unable to locate, or consist of federal prohibitions only (meaning CA DOJ is unable to prosecute as the person’s prohibited status is a matter of federal concern).

Of all the 14,515 individuals placed in the pending category, CA DOJ’s report claims 5,322 were placed there due to enforcement efforts in 2020. The remaining 9,193 were thus placed in the pending category prior to 2020.

CA DOJ did not begin reporting on the number of pending cases until 2018. And it wasn’t until the 2019 report that CA DOJ gave more detailed information as to the exact reason an APPS case was listed as pending. That said, the exact number of pending cases has remained relatively constant since 2018, first reported at 13,818 and then 14,677 in 2019.

When we add the number of “unable to clear” cases to those cleared only because DOJ’s AFS database was inaccurate or otherwise out-of-date, DOJ effectively wasted their time and taxpayer resources on over 6,901 cases. That number is likely much higher because it assumes every single firearm seized was connected to a separate APPS case—which is certainly not the case.[7]

The above examples of declining efficiency can, of course, be explained to some degree should it be shown the number of agents and employees working APPS cases is similarly declining. But that number has remained relatively constant.

In 2020, CA DOJ increased the number of agents working on APPS to a small degree, with a total of 50 agents and trainees dedicated to APPS. Although the exact number of agents has fluctuated over the years, the APPS program has averaged around 55 dedicated agents and employees every year.

Conclusion

While CA DOJ’s report attempts to cast the APPS program in a favorable light, a detailed analysis paints a different picture. CA DOJ has attempted to explain the drop in results for factors outside of its control, largely due to COVID-19. But the effectiveness of the APPS program has been declining since its inception—well before the pandemic.

More importantly, none of the case examples provided by DOJ in the report suggest the individual was misusing their firearm(s) or had any violent intentions. Instead, their only crime appears to have been caught up in the myriad of gun-control laws labeling them a “prohibited person” by the state of California.

Perhaps California’s limited law enforcement resources would be better spent addressing the actual criminal misuse of firearms, or even better, educating California gun owners on the knowledge, skills, and attitude necessary for the safe and legal use of firearms.

Matthew D. Cubeiro is an attorney with Michel & Associates, P.C. who regularly works on firearm-related issues for the firm’s clients. He is also an NRA certified instructor and Range Safety Officer.

Links to Available APPS-Related Reports

- California State Auditor Report Regarding DOJ APPS Program- https://www.auditor.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2013-103.pdf

- 2014 APPS Report (Report #1)- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/armed-prohib-person-system.pdf

- 2015 APPS Report (Report #2)- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/armed-prohib-person-system-2015.pdf

- California State Auditor Follow-Up Report Regarding DOJ Delays in Fully Implementing Recommendations for APPS Program- https://www.auditor.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2015-504.pdf

- 2016 APPS Report (Report #3)- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/armed-prohib-person-system-2016.pdf

- January 1, 2016 SB 140 Supplemental Report of the 2015-16 Budget Package Regarding APPS- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/sb-140-supp-budget-report.pdf

- 2017 APPS Report (Report #4)- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/armed-prohib-person-system-2017.pdf

- 2018 APPS Report (Report #5)- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/armed-prohib-person-system-2018.pdf

- 2019 APPS Report (Report #6)- https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/publications/apps-2019.pdf

- 2020 APPS Report (Report #7)- https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/attachments/press-docs/2020-apps-report.pdf

[1] Senate Committee on Public Safety, April 24, 2001 hearing on SB 950.

[2] CRPA challenged this unlawful use of DROS funds in the case of Gentry v. Becerra, which in 2017 resulted in an important ruling reigning in CA DOJ’s use of these funds. Litigation in that case is still ongoing.

[3] The newly implemented reporting requirements have been codified in Penal Code section 30012.

[4] A printout of the information being submitted is provided to the prospective purchaser by the dealer.

[5] For example, AFS has been designed to treat any variation concerning a firearm’s description as a separate firearm. Should an individual later sell their firearm to another person and the dealer enters a description of the firearm that varies from the original record in terms of color, barrel length, or otherwise (despite the firearm’s serial number matching exactly), AFS will treat the transfer as involving a different firearm from the one originally purchased.

[6] DOJ’s report includes a breakdown of the types of firearms seized. The majority (464) were handguns. Only 37 were classified as “assault weapons,” and another 35 were non-functioning firearms in a receiver/frame only configuration.

[7] DOJ’s own report provides several “case studies” in Appendix G. Such studies provide examples of how a single individual listed in APPS was found to be in possession of more than one firearm. The case studies include examples of 10 firearms, 12 firearms (11 of which had been given “to a friend for safekeeping”), 19 firearms, 4 firearms, 8 firearms, and 1 (with another 7 unaccounted for), respectively.

Wasting tax dollars? Welcome to CA.

Years ago, CADOJ literally arrived at my door to serve a warrant that had been ordered due to their belief that I was illegally in possession of a certain firearm. After a discussion on my driveway, they mentioned they had no paperwork in their records of my original purchase. I was a bit dubious of this, and presented them with my own copy of the DROS. Upon review, the agents declared that all was well and the left me alone.

I asked the supervisor how CADOJ could have “lost” their copy, when there should be (at the time of purchase) both paper and digital versions on file, and he admitted there are so many mistakes in the state’s systems, they can’t keep up.

So I believe this article. CADOJ is too big for their own britches and have too many errors to cope with. Underscores the opinion that all registration should simply be abolished.

Finally a state worse than ILLinoyed…sorry guy’s!🙁

So this is both bad news and good news.

Bad: California has a government registration and confiscation system.

Good: Like most “progressive” schemes, it mostly doesn’t work.

Bad: California’s registration-and-confiscation scheme, like most “progressive” programs, is a massive waste of public money.

Good: A wasteful, mostly nonfunctional registration-and-confiscation scheme is much better than a functional one.

Bad: Gun owners have been forced to subsidize their own harassment.

Good: The government can’t/won’t give its engine of tyranny the funding to make it effective.

Bad: California’s stupid “progressive” ideas tend to ooze out into the rest of the US.

Good: This particular idea would surely make more Americans hate so-called progressives and their wasteful, repressive rulemaking.

I may be wrong, but my understanding is that the entire suystem is funded by DROS fees–i.e. by gun purchasers paying into the system. This is why the DROS fee went from $25 (which was more than the cost of running the DROS system, which was the purpose of the fee, generating a surplus)to $37.17.

Technically, there is no gun “registration” in California, but that is more than a technicality. Unless one has at least one firearm in the system (i.e. “registered”) one cannot buy ammo except with a full blown $37 background check. If there is at least one firearm, then the fee for the minicheck is $1. But this too is problematic. That firearm has to be registered to your current address, so if you move, those prior arms won’t count. Further, once in, you are never out. So for example you are in the system but sell that firearm. A new record is generated but the old record is not deleted or amended to show that you no longer own that firearm, even if you file paperwork in your own name of the sale, filling the system with “false positives.”

Not only does this make a difference for APPS, but if you suffer the seizure of a firearm, if for one of the foregoing reasons it does not show up in the system, you will be charged with having an noneregistered firearm (funny how that is) and your firearm seized.

Please provide supporting link(s) for automatic charge of “having a non-registered firearm”. There are multiple ways a person may legally be in possession of a handgun in CA without registration. If you owned or received it by transfer before 1991, or intrafamilial transfer before 1993. If you assembled it yourself and serialized it before July 1, 2018. Etc.

All of this is by design. There are so many laws that they can lock anyone up, it is selective enforcement. This way, if they don’t like what you are doing(it is perfectly legal, but is stepping on some VIP’s toes or is throwing a wrench into the works of a “special” program), they will just find a reason to harass you. They could come and take your firearms(which makes you look like a mental case to the public) or they can arrest you for violating a law that was written for a different reason. The way these laws overlap, there are many shades of grey, but the state’s attorney can turn those bright flaming red and convict you.

Face it…If they are not stopped cold the Rats behind Gun Control are inching their way to all firearms. And how is that happening? Because Gun Control hides behind a media smiley face and has never been properly defined as an agenda rooted in racism and genocide as history confirms it to be.

Here you have the name Cleveland Indians being changed to Guardians because just using the name “Indian” is Racist. Well when it comes to Racism and American Indians Gun Control is much, much, much more serious than the name of a f-n Baseball Team. Where are the do-gooders with Gun Control and The American Indian? And where is their call to rip The 1968 Gun Control Act from the pages of congress?

And when are those on radio and elsewhere who present themselves as defenders of The Second Amendment going to step up and define Gun Control for what history confirms it to be? When it comes to the Biggest Race Based Bigoted Turd In America called Gun Control such defenders are suspiciously silent. Who or what are they afraid of? Hopefully such defenders do a better job should they hear a neighbor beating his wife.

Yeah, Debbie’, but soon they’ll see light at the end of the tunnel but it’ll be too late to make it out.

They are so emboldened by all these Gun Control efforts actually gaining ground with ‘nary a whimper’, at least not in the form of an outright outrage in the form of heavy media protest or even protest marches at appropriate locations, sponsored from all these so-called big anti gun groups l I mean let’s face it, with the exception of a couple of Pro-2nd/A orgs who Do NOT subscribe to compromise of any kind like GOA and Firearms Policy Coalition, who actually do court challenges, Big shots in the NRA seem to spend more of your money on their own Corporate elections and other bullshit than they do on fighting the evil enemies of our Consitution?

So now the rights killers just launched the latest beta test to an upgrade to their parallel destruction of the 1st/A by allowing Facebook to censor and ban so-called bad speech or organizations, that in their disease-ridden brains amounts to the socially dangerous act promoting of 2/A sanctuary states from proliferating! The Michigan pro 2/A sanctuary state movement has been shut down from Facebook because Facebook simply decrees that it is some kind (actual phrase escapes me at the moment due to enraged state of mind) domestic dissident type unacceptable content problem that goes against its policy!

Essentially, this amounts to what the EFTAB is doing with unconstitutionally illegal gun rule restrictions and prohibitions arbitrarily being enforced. Fuckface-book now thinks it’s its own law-making Congress also!

So where’s the outrage? Nowhere in the mainstream moron media? There’s more bullshit news about Olympic assholes playing with themselves than one of the most important issues of our lifetimes?

Yeah, it’s certainly scary that we now realize in shock and fear that the deep state Marxist movement has been using ‘color of law’ to make unconstitutional illegal criminal code laws in their agenda based plans since the 1934 NFA through the chopping block of the ’68 GCA, the 86 Firearms protection Act, (an oxymoron in that they actually sneaked in MG bans).

Registration, last I checked, of personal private possessions like 2nd/A firearms is supposed to be prohibited for the Government? And the reason for that law, is ONLY to prevent diarming the public by knowing who has guns and where to locate them! We The People have an unassailable Constitution written in stone that is all about Prohibiting what the government can do. NOT about prohibiting what the people can do when it comes to rights!

So how the fuck did we let them get away with turning THAT fundamental critically essential tenet of our American way of life, liberty, and justice into quite the opposite?

Well, that’s another expanded topic we’ll surely get into before it’s all said and done, but the fact itself is now bitch slapping us in the face and laughing all the way home. they got away with it and are now getting away with it more!

It’s scary shit but you know what’s even more frightening than Stasi illegal firearms regulations and registration, 4th/A violating home-invading criminal police raids to Confiscate your Guns, and continuing the police state-style enforcement of Unconstitutional not binding laws under(Marburry v. Madison, Miller v. U.S.)?

This APPS was a precursor to the tactical disarmament program they have planned. They knew in advance it wouldn’t work well. They just wanted to see how it went so they can improve the efficiency of actual door-to-door confiscations. And Not necessarily of Active career criminals and gangs. They don’t really care about these reprobates. ‘Good’ police work, and even more importantly an Uncorrupted Justice system can diminish violent crime considerably if they wanted to. But they need their crime committing publicity factor as a continuous justification for their MASS confiscation populaltion disarming agenda.

That’s What’s coming soon…to a theatre near you..if they continue to get away with unaccountability for committing felonies in violation of our Constitutional rights.

Let’s pro-actively support these 2nd/A Sanctuary city efforts and the Constitutional Carry States while gearing up for the only way we can beat them ultimately next year in the midterms. The campaign has begun. Visit your local political party office and volunteer your time if you can’t afford donations to GOA or Firearms Policy Coalition, etc. and…

Urge your State reps to pass Constitutional carry in your sate and support Sherrif Mack’s Constitutional Sherrif’s organization by donations or joining, to make sure your Sherrif is bound to his sworn Oath and going to protect your Constitutional rights against all these illegal laws they’re getting away with enforcing or elect somebody who will!

And if we don’t do that…

Well…I can’t even imagine that at this point…

The tyrants who run California have figured out that if you give enough people in the state “their toys and fulfill their darkest wishes” the majority will vote for tyranny. And it’s not just about drugs and sex.

There are a lot of Californians who want to be taken care of by the state. In other words they want other people to take care of them, through the power of a government taking from productive people. And then giving to people who refused to take care of themselves.

The majority population in California has lost its moral compass. And the people with the ability are leaving the state. Unfortunately some of them are bringing their liberal politics with them.

The people who are leaving Ca are either the biggest winners(those that own big companies) and the losers(those that couldn’t stay in the middle class here. Sadly, the government is allowing those that lost almost everything to camp on the beach, streets, parks, and other public property designed for other use or squatting on private property.

For the most part, those leaving Ca did not start here. They are the problem, they have turned this state into what it is now. The families that have a legacy here(100 years or more) are not leaving in droves and do not support those now in power.

My family’s Heritage has been traced back to the time gold was discovered in California. Growing up in Sacramento in the 60s and 70s I remember all of The Outsiders coming to California. And all of them that I talked to, all told me they came because California had the best welfare of all the 50 states. And California also had the most generous government benefits to pay for going to college.

California was flooded with the nation’s lazy, lay about’s, and the rest of the other states hedonistic people. This way they could come to California and continue in their self-destructive lifestyles. All supported by the rising state taxes.

All that disgusting word salad……

SHALL NOT BE INFRINGED….. BUNCHA JOGGERS….

When it comes to government nothing is a waste of tax dollars.

The $165,000 shovel that stands on it’s own replaces an average of two to three county workers.

I left that filthy manure wagon in 1971 and have only one regret; going there in the first place. Maybe we could sell it to pay the national debt, thereby solving two problems. Does Mexico want it back?

Comments are closed.