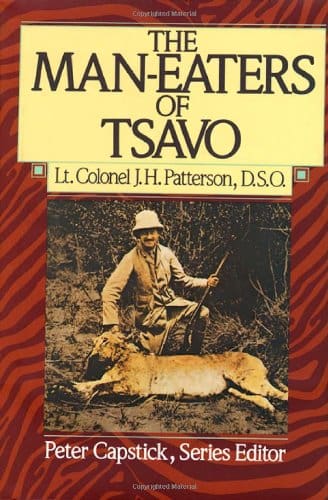

I have not encountered a more thrilling rendition of living, working and hunting in Africa than is found in J.H. Patterson’s The Man-Eaters of Tsavo. It is one of my most cherished books.

It is also a book with an incredibly misleading title.

Don’t misunderstand me. Patterson gives a marvelous description of his dealings with the two male lions that ate 28 railroad workers and who-knows-how-many native Africans. However, he relates this portion of his experiences to a mere seven of the 27 chapters (approximately 70 out of 350 pages).

The remainder of Patterson’s text paints a wonderful tale of traveling and hunting in the East African wilderness. I honestly enjoyed the 20 remaining chapters as much, or more, than the seven occupied with the battle to rid the area of the man-eating lions.

Patterson doesn’t come across as an arrogant individual. In fact, he relates all of his adventures in a self-deprecating manner. So I can imagine that when he delivered his manuscript to his publishers, it might have carried a different title; maybe the author’s suggestion was My Time Working as an Engineer in East Africa.

If so, and having dealt with book publishers myself, I can imagine them rolling their eyes and stating sarcastically “Oh, yeah, that title will really make people want to read this book!” The publishers would have then put a thick red line through the author’s suggested title and written Man-Eaters of Tsavo in its place. And, history was made.

Again, I don’t mean to minimize the wonderfully exciting and harrowing tale of how Patterson hunted down and killed the two man-eating lions. The great F.C. Selous was interested enough to write the forward to the book, stating “…no lion story I have ever heard or read equals in its long-sustained and dramatic interest the story of the Tsavo man-eaters as told by Col. Patterson.”

That’s wonderful praise when one realizes that it came from that period’s dean of African hunting.

I won’t presume that I can give praise with the same weight of Selous’. Instead, I’d like to mention two of what I like to call Patterson’s “Hold my beer, and watch this!” episodes which may give you a flavor for what he’s written here.

There are many, many more, causing Patterson himself to conclude, “…it was much more likely that [the man-eaters] would have added me to their list of victims than that I should have succeeded in killing either of them….”

That Patterson includes these episodes for his readers seems to indicate some measure of honesty and humility.

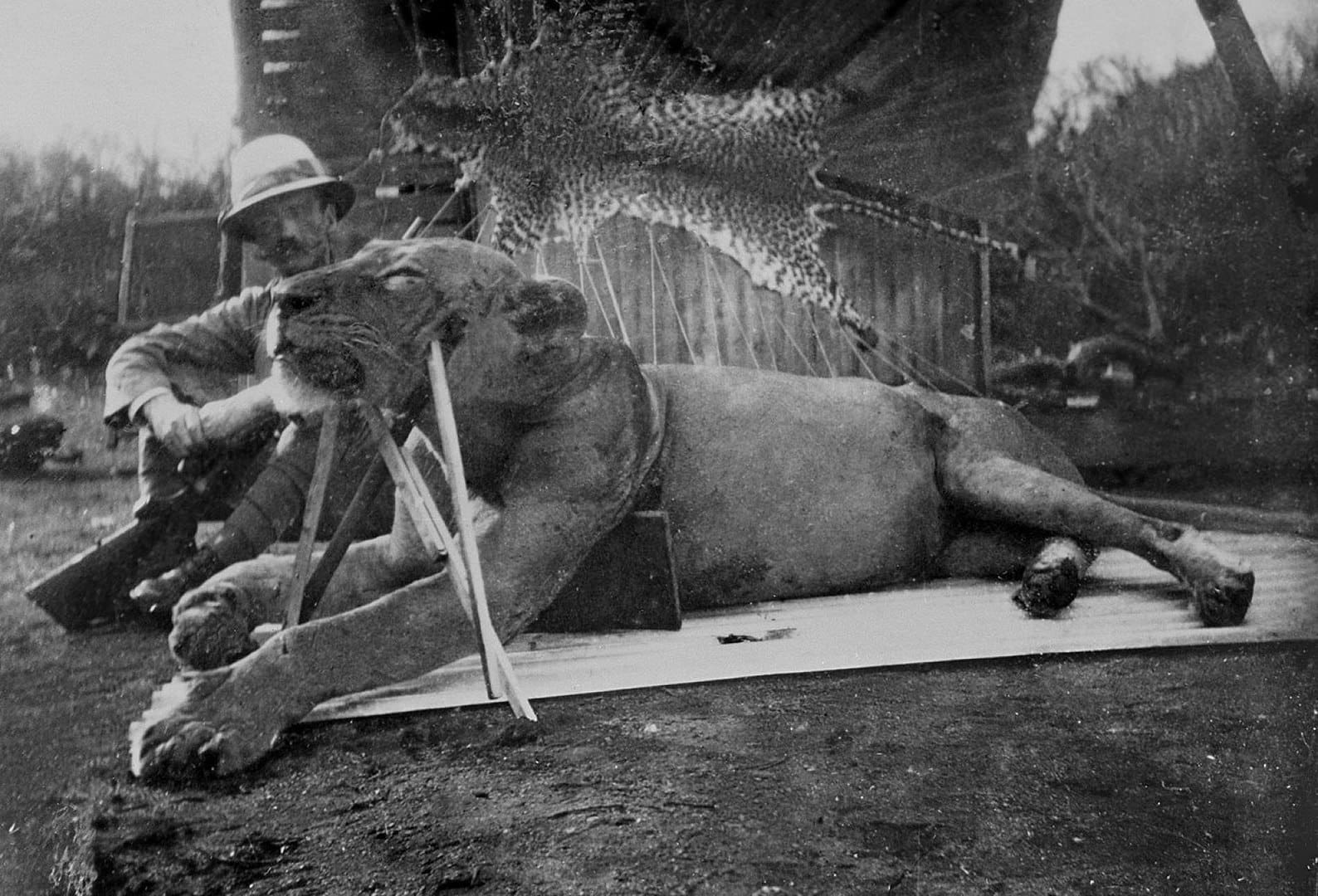

- On the night Patterson shot the first of the two man-eaters he stationed himself within leaping height of the lions on a rickety perch that an aggressive moth could have toppled. One of the lions appeared and began stalking the hunter-cum-prey. In Patterson’s words, “…the staging had not been constructed with an eye to such a possibility. If one of the rather flimsy poles should break, or the lion could spring the twelve feet which separated me from from the ground…the thought was scarcely a pleasant one.”

- Patterson insisted on hunting dangerous game (including the man-eating lions) with what many would argue was an exceedingly light caliber for such species, his .303 rifle. One particularly telling event involved him stalking a rhino, it charging him, his shooting the rhino with the hope of turning its charge, but only irritating the rhino further. He then threw his pith helmet to the side and dove onto the ground to lay there while the rhino beat the hell out of his helmet. He then breathed a sigh of relief when the rhino retreated, heading away from where Patterson was on the ground. But, as the author relates “…I could not resist the temptation of sending a couple of bullets after him.” The result was predictable: “…for directly he scented me…and down he charged like a battering ram.” After tearing up all of the real estate with horns and feet – except for that occupied by Patterson’s trembling form – the rhino once again departed. This time Patterson chose not to pop the retreating animal in the fanny.

As I mentioned, 20 chapters of Patterson’s book are filled with wonderful vignettes of living, working, traveling and hunting in late-19th abd early-20th century East Africa. I commend this work to any who are interested in tales of adventure, suspense, slapstick humor and courage.

The Man-Eaters of Tsavo is one of my go-to books when I want to dream of a life well-spent in the pursuit of daring exploits. It also acts as a valuable reminder of some of my own “Hold my beer, and watch this!” foolishness.

A primary reason for the man eaters ability to eat so many men was the .gov’s need to disarm the native peoples. When you have the boot on the neck of the population it is not wise to allow them firearms.

Large swaths of Africa, India and Asia the local folk had to cower in fear and await rescue by the great white bwana whenever an animal or bandits decided to take advantage of them as victims.

In modern times the great white bwana has morphed into the socialist.

You know, not every article on TTAG is about you and your personal boogeyman? Right?

Says the guy that has a raging case of TDS.

You know, not every article on TTAG is about you and your personal boogeyman? Right?

Says the guy that has the raging case of TDS.

This… escalated quickly…

Escalated quickly? Oh, wasn’t that bad. The man-eating lions tho, that was really bad.

Dragging current day American politics into discussion about a book by a famous British adventurer of over a century ago is just kind of weird.

Just pointing out the obvious connections between disarmed and helpless natives dependent on the .gov for their very lives and what modern socialists are attempting to do in America.

First and foremost this is a gun site and you cannot untangle guns and politics. The left gets their panties in a twist when you point out the similarities in historical tyrants and them. So enuf tries to censor my comment.

Note that there are no reports of the chicoms now infesting East Africa being eaten (by lions or pissed of natives). The aliens from Peking having recently replaced “the great white bwana” in running the cesspool.

Not that the movie is accurate but I just recently rewatched The Ghost and the Darkness a few weeks ago. This book is on my list to get to in the near future. Gotta love the .303 🙂

I don’t remember the exact source but i read about Tsavo in my youth. When the movie came out I went to see it and I have it in my collection of dvd’s. It’s not accurate but it’s still a good movie.

I really liked my Lee Enfield in .303. Had an Indian Ishapore, more than one, in 7.62 nato. In that action type I prefer the .303. May just be the history buff in me.

You would be surprised what calibers the professional hunters and guides often used. The 6.5 Mannlicher Shoener (Dutch) and 7mm Mauser were among the most common. Others would use local military calibers to get ammunition from local garrisons.

Meh. The lions were right.

The lions said the natives tasted like chicken.

Swarf, man eaters are alive and well in Africa and India. If you like ’em so much; why don’t you trot on over there, sans rifle, and sleep in the open?

What’s not to love?

Esoteric Inanity once knew a “man eater”. She was of the Irish persuasion, rather than African or Indian. But alas, not wife material Due to her voracious appetite for “man eating”.

A man dare not “sleep in the open” with her on the prowl.

I read this book long before the movie hit the theater. As is most often the case the book was better. In fact, the author’s review was modest. I have only one reason to visit Chicago. To see the Lions of Tsavo in the Field Museum.

Saw them there several years ago. I didn’t know the story at the time, but seeing them impelled me to learn more.

The chapters on the lions appeared in a magazine serialization my father had in the 1960’s, which is the only part of Patterson’s book I have read. When “The Ghost and the Darkness” movie came out, knowing the true story it was disappointing to see an extra character added to save the day. That he then gets killed by the lions in the middle of the night with no one noticing was just sloppy writing.

The real story of Patterson and his accomplishments was far more interesting.

Man Eaters Camp

https://goo.gl/maps/Kh8SpfsGtAvZ7UUU8

http://www.maneaterslodge.com/

Good book. Many feel that the sickness, death, and casual disregard of the bodies helped to develop the man eaters taste. As lions would much rather prefer scavaging than live prey, dead don’t tend to fight back. The habit of 6 feet under would apply to this situation very much. If you like this book, I would highly suggest Peter Capstick’s “Death in long Grass” and “Death in the silent places.” Silent places talks almost exclusively about man eaters the world over and who corrected them. I remember right, it was a bengal tiger or leopard in India that had racked up over 400 hundred that was known of. 400! Jim Corrbet finally corrected his “manners”. Tales of a South American hunter who used a shortened spear to hunt because it was much faster than a gun. Long Grass is a book of his personal stories from his time of being a professional white hunting guide in Africa hunting the big 5 and a few chapters of animals that can really ruin your day. I’ve learned some trivia that I’ve even used while watching Jeopardy and friendly games. All three are good reads

I read this volume 10+ years ago, and again 5+ years ago. Very well written. Captivating story.

Michael,

Next you should review “Death in the long grass” by Peter Capstick.

God bless that book. I bet I’ve read it 12 times. Turned me into a Capsticke junkie! I can’t get enough of his work.

CAPSTICK. Damn autocorrect.

One thing I learned from Capstick’s books is that when things go wrong on a big game expedition they can go VERY wrong ….for the hunter.

Great idea. That is one of my favorite books of all time.

I’ve even got a number of copies of it, one a 1st edition.

Anyplace there is used books i always look for his work, Death in the Long Grass will be just the start of a multi-week reading adventure as you end up searching out all of his works.

I you want to travel to Africa, and can’t afford it, read Capstick as he will put you there.

Just to add, Robert Ruark has a couple of good ones as well (Horn of the Hunter to name one.).

.

Patterson’s book has long been a favorite of mine. I highly recommend it…not that anyone here has any particular reason to value my recommendation (-:

For those with limited means, you can click HERE to read it in .pdf for free.

Full URL:

http://feagraduate.org/The%20Man%20Eaters%20of%20Tsavo%20by%20J.H.Patterson%20(Adventure).pdf

Oops. That “full URL” is too long and was truncated. Add “.pdf” (without quotation marks) to the end if it doesn’t work for you.

This book belongs on every hunters bookshelf. Its classic Africana. It gives one a look back at the Old Africa before it went the way of most countries with modern cities and crime and of course the near extinction of its wildlife.

Patterson while guiding a man and his wife on an African Safari had a lurid affair with the man’s wife and his client ended up dead under very mysterious circumstances. Ernest Hemingway’s book “The Short and Happy life of Francis Maycomber” was based on the lurid Patterson affair. There was a 1947 movie about it called “The Maycomber Affair”.

Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, DSO (10 November 1867 – 18 June 1947), known as J. H. Patterson, was a British soldier, hunter, author and Christian Zionist, best known for his book The Man-Eaters of Tsavo (1907), which details his experiences while building a railway bridge over the Tsavo river in British East Africa (now Kenya) in 1898–99. The book has inspired three Hollywood films – Bwana Devil (1952), Killers of Kilimanjaro (1959) and The Ghost and the Darkness (1996) in which he was portrayed by Val Kilmer.

Often when reading old hunting books on Africa and India the authors will often refer to some of their favorite hunting books, some now so rare the Libraries often will not lend them out. I often had Librarians ask me “Where do you come up with these very old and rare book titles”?

Other great authors of Africana would include Percival, Stigand, Lyell, Foran, and of course John Boyes who wrote the great African Adventure book “King of the Wa-Kikuyou” Although Boyes was not a hunter but rather an opportunist his adventures in “old Africa” are so thrilling its a dam shame they never made a movie about his book. The part I remember most about his book is when he tried to impress an African King that he wanted to trade with by presenting him with the most modern hand gun of the time a “Mauser Broomhandle Pistol”. The King who lived about as far out in nowhere as you could get laughed when Boyes gave him the gun and said ” This is a nice pistol but I am sitting on two of them underneath by seat cushions” which shocked the hell out of Boyes.

Agnes Herbert wrote 3 great hunting books back in 1900. Casuals in the Caucasus, Two Diana’s in Africa and Two Diana’s in Alaska ( the Alaska book is still being printed in paper back). Its as popular today as it was 119 years ago, perhaps even more popular today.

My comment ( in its totality) would have been only about 1/3 of yours. Thank you for the 2/3 tutorial!

My favorite all time book on Africa (besides Jim Corbett’s tiger hunting books) was called “Hunter” by John Hunter. Hunter was a real cock hound and seduced many of the wives of his clients. He got such a bad reputation that many men refused to accept him as their White Hunter because they were terrified he would end up banging their wives. Rich European women often offered him huge amounts of money if he would marry them. Hunter was often offered his pick of young African beauties as a return favor to many African Kings when he stayed at their villages and shot off marauding beasts that were terrorizing the local community.

During Hunters much later game control work he shot thousands of the most dangerous beasts in Africa to make way for clearing land for new African farms so the dangerous game was simply exterminated. His lion hunting adventures were most hair raising as well as his rhino and elephant hunting.

Hunter was once offered the fabulous game rich Ngorongoro Crater teeming with big game for a price that was next to nothing but since there were no roads at that time to the place he turned the offer down. The place would have made him in later years a millionaire.

I do not think there will ever be a movie about John Hunter the movie would be too controversial even these days both to people in Africa and Britain and of course the rabid anti-hunters would shit a brick and boycott the movie.

Patterson’s book and two by Robert Ruark informed my youth about Africa. The Tsavo lions killed about 28. The Mau Mau were more prolific. The British couldn’t count the number they killed.

I’d rather face the lions.

Everyone with an interest in the subject should read this book, and EVERYONE needs to read Peter Hathaway Capsticke. Been digging Steve Rinella lately as well.

CAPSTICK.

The fictionalized movie version of the Book is The Ghost and the Darkness. The movie is done quite well but they do take liberties expanding the plot and adding characters. Worthy of your time.

Just a heads up; this book is available on Amazon in Kindle format for 99 cents.

https://www.amazon.com/Man-Eaters-Tsavo-Illustrated-Henry-Patterson-ebook/dp/B00J0L72R4/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

an opposing comment, the film with kilmer and douglas was terrible.

Reminds me of the movie “The Ghost and the Darkness”.

The Tsavo lions were copy cats.

Col. Coopers tales of hunting Africa sparked my imagination and lead to my first pilgrimage to the Dark Continent. I read everything published by Cooper who led to the writings of other adventurers and hunters. My first trip was to Rhodesia (for the PC crowd Zimbabwe). The culture over there has “progressed” but I walked the same terrain and perhaps took lunch and rested out the afternoon heat under one of the same baobab trees that earlier travelers stopped at. African hunting to me is an obsession I’ll list the writers I’ve read and maybe it will save someone some time researching, I own and have read every book by every author listed if they have multiple books I’ve read them all.

My list – Lindy Cooper-Wisdom, Jose Ortega y Gassett, Charles Cottar ( a fellow Texan), Theodore Roosevelt, Peter Capstick, Ernest Hemmingway, LTC. Robert K Brown, Maj. Frederick Russell Burnham, (for those in Calif. his family plots are in Three Rivers, Ca., once you’ve read about the man a worthwhile visit), J.A. “John” Hunter, Gerard Miller, John Taylor, Paul Kruger, Elmer Keith, Terry Irwin, Col. Craig Boddington, Finn Aagard, Martin Dugard, Jack O’Connor, Baron von Finecke-Blixen, Robert Ruark, Deneys Reitz, Walter Dalrymple Maitland (W.D.M.) Bell, Frederick Courteney Selous, Daniel W. Streeter.

Forward does not equal Foreword, which is what Selous actually wrote. Little known fact: when King George VI died, it was Colonel Jim Corbett (who had relocated to Kenya after Indian independence) who woke up the Royal couple and told the new Queen Elizabeth that she was now the monarch. This was while Elizabeth and Phillip were on their honeymoon at Treetops in Kenya. So they had to pack up their little safari and decamp to England.

Comments are closed.