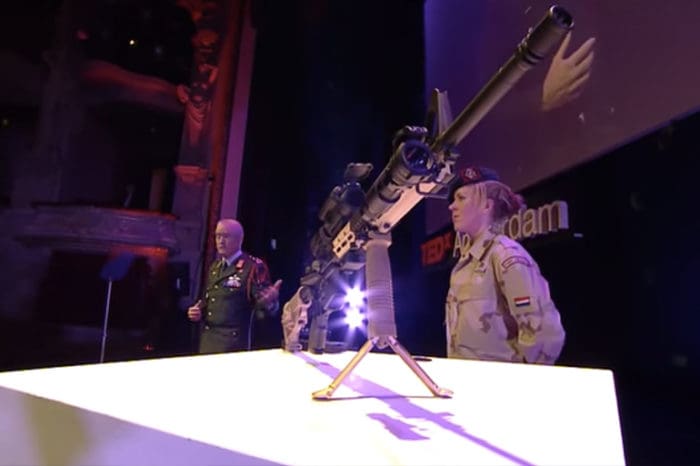

When one reads gun blogs voraciously, one runs across two main types of arguments for our right to keep and bear arms (RKBA). The constitutional argument (the English comprehension model) and the self-defense argument. I have a broader theory, though. The idea hit me when I was watching a TEDx talk by General Peter van Uhm, former Chief of Defense for the Netherlands’ armed forces.

I began to think of a more salient correlation between weapons, personal freedom and democracy. The working theory: firearms are related to the rise of democracy, representing a basic subversion of the dominant political theory of government.

To examine the relationship between firearms and the subversion of tyranny, one must go back to the beginning. For democracy that means Athens.

At the time when the political system arose, Athens was a gun-free zone. Socrates wasn’t leaning on his long rifle on the Promenade as he taught. But when nascent democracy granted its citizens (a rather select group) voting rights, it required military service. Conscripts had to provide their own arms.

The average Athenian citizen owned his own sword, spear and armor. He was trained in their use during weekly drills in phalanx fighting (as well as participation in the “manly” sports of wrestling and boxing). Given the geopolitical conditions on the Greek peninsula of the day, it’s highly likely citizens had plenty of actual combat experience as well.

Athens had a democratic political system. They also had democracy of violence, in that all citizens (once more, not the same thing as a modern citizen) had ready access to weapons and training. It becomes a chicken and egg question – which came first? I’d hazard the guess that the blades came before the ballot.

The fall of democracy, the rise of empires and the greatest inequality in political power ever seen followed with the Roman Empire, and on into the Dark and Middle Ages. Technology outpaced income. The average citizen of Rome, and what’s now Germany and France could no more afford state-of-the-art weaponry than an average American can now afford a tank. Even for nobles, the cost of weapons and armor prepresented years of income. They were totally beyond the reach of the common man.

Notice what emerges at roughly the same time as the rumblings of the Renaissance. Two weapons, both cheap, which allowed a commoner equal footing with a knight: the crossbow and the longbow. The papacy and many kings tried to ban the crossbow, horrified that a peasant with a cheap weapon could kill a highly trained soldier. Richard the Lionheart, that famous conqueror, met his end at the point of a crossbow bolt from some low-level grunt.

The only nations to embrace the new technology fully were the city-states of Italy. The Florentines, for example, made crossbow practice a national sport and fielded mercenary armies of crossbowmen who fought in wars across Europe. England was the other early adopter. The Brits mainstreamed the longbow, and met with great success against the French in the Hundred Years War.

The political process in both countries, the latter of which created the Magna Carta, reflects this democratization of violence. In short, an armed and trained populace demands more political freedoms.

The advent of the firearm hastened this process. The over-extension of colonial empires encouraged rebellion. The distances provided the space to learn self government, but the harshness of the new world and the necessity of personal defense weapons brought a new sort of populace.

—–

Even counting the risk, even with the most apocalyptic predictions our opponents can dream up, the democratization of violence is an almost unqualified human good.

—–

The average American of the eighteenth century may not have been much more educated, healthy or wealthy than his British counterpart, but he knew his way around a musket. He’d drilled on the village green with his neighbors. They were nothing like a trained military force, but they did have basic infantry skills and at least on a personal basis, their weapons were a match for any in the world.

Correlation is not causation. I don’t want to overstate the case here. Dozens of important factors led to the rise of modern democracy, including the advent of the printing press. But I do think that the availability of relatively cheap weapons — which are at least comparable to proper military arms — are part of the primordial stew that breeds a free political system. And, I like to think, maintains it.

Ask a political science professor what constitutes a government and he’ll likely describe it along the lines of an organized monopoly on the legitimate use of force. There are some permutations, but this is the basic thrust of the idea of what a government is. Except it’s not true.

Governments are most free when they don’t have that monopoly. I mentioned Athens, Britain, Florence and America, all states which achieved great political freedom with a well-armed populace.

Now, we could get into a hair-splitting contest over the word “legitimate,” but I doubt there’s a legion of PS profs to take me to task here. When a government encourages/allows an armed citizenry, it legitimizes their access to the tools of violence.

Firearms represent the ultimate democratization of violence. They’re the great leveler. What is the old saying? “God created man, but Sam Colt made them equal.” A gun is of the greatest benefit to the weakest in society.

A sword is deadly, but requires a fair amount of strength, skill and training to use one. A bow requires upper body strength and a lot of practice. A gun…well, one needs training to use one properly, but the basics are easily attainable with a quick lesson.

I’ve seen this process a hundred times and I can tell you this; I can take a person who has never touched a firearm and get them handling it properly and hitting their targets in one short session. Sure, a shooter needs a minimal amount of hand strength, but even a heavy trigger is usually under ten pounds. Virtually any human being who can drive a car or ride a bike can use a firearm. Even those with severe disabilities can usually manage one.

Of course, with any tool there are risks, small though they may be. Democracy isn’t always pretty, and it doesn’t always follow the course we’d like. Still, the evidence is undeniable that gun owners – as a group – are a remarkably peaceful and law abiding lot. There will always be the small minority who can’t manage their freedoms responsibly. But much of our position today is due to the emphasis put on training and safety in the gun rights community.

I put it to you thus: Even counting the risk, even with the most apocalyptic predictions our opponents can dream up, the democratization of violence is an almost unqualified human good. It’s a basic question of equality. All men and women may be equal before the law, but how are people to be equal in the face of violence?

It’s men who would have the advantage, and younger men in particular. I say this as one whose position would be least improved by the addition of a firearm. Were all society to be disarmed, my relative position in this continuum would be improved. I am relatively young, fit and have the advantage of military training.

I don’t hold this position out of fear of other people. I’ve seen the elephant in the room. I believe that the broad public ownership of firearms is a positive societal good, for my sisters, the service men who came back short an arm or leg, the minorities threatened with violence by the intolerant and the urbanites dealing with the meltdown of inner city society (I live in Michigan, I know of which I speak).

A firearm is literally the power of life and death, and while some may fear having that power distributed to the furthest reaches of society, I do not. I fear the concentration of that power.

This post was originally published in 2012.