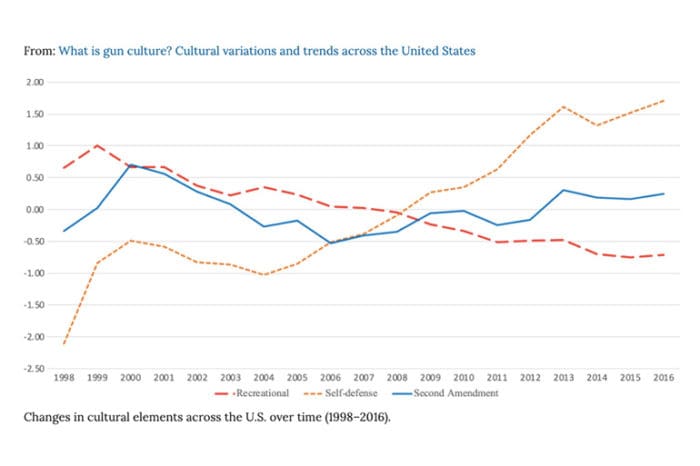

As the abstract for this bit of sociological analysis puts it, “This paper advances the literature on gun culture by demonstrating that: (1) gun culture is not monolithic; (2) there are multiple elements of gun culture that vary substantially between states; (3) over time, the recreational gun subculture has been falling in prominence whereas the self-defense subculture has been rising; and (4) there is another subculture, distinct from the self-defense one, which consists in mobilization around the Second Amendment and was strongest in places where state firearm laws are most extensive.”

The three components that we identified can be considered to be “cultural” according to the definition used in our analysis. For example, Kohn found that recreational or sporting subcultures, such as hunting, target shooting, or competition shooting “signify certain kinds of values, traditions, and/or ways of life that those gun owners see as part of their cultural heritage” (Kohn, 2006, p. 15). Both Stroud (2016) and Carlson (2015a) showed that ownership of guns for self-defense is not merely pragmatic, but is associated with an entire set of symbolic meanings that encompass personal identity, masculinity, power, freedom, racial attitudes, responsibility, morality, and views of governmental threat.

The right to bear arms has been portrayed, largely by the NRA, not merely as a Constitutional right, but as the right from which all other rights and freedoms flow (Keene and Mason, 2016). As expressed by Keene and Mason (2016), “the real fight [about the Second Amendment] is not about this restriction or that law, but about the nature of American culture”.

The presence of a distinct cultural element centered around Second Amendment activism is consistent with previous literature which showed that there exists a movement that does not view the defense of the Second Amendment as a means to an end, but that believes in the importance of gun ownership per se. As 12-year-old Texan boy Ashton puts it: “I like guns because they don’t just represent hunting, target practice or competition. They represent freedom in the form of self-defense or in the case of the Second Amendment it means protection from the government” (Badessi, 2019).

This theory that the Second Amendment is necessary to all other freedoms was explored by Anderson and Horwitz who showed that the NRA has embraced insurrectionist ideology (2009). Our finding that Massachusetts and Connecticut are low in the recreational element and high in the Second Amendment one seems to substantiate their claim.

About New England, they write: “the link between these original citizen-soldiers and their guns has been carefully preserved at a host of Revolutionary War battlefields, monuments, and museum exhibits” (Anderson and Horwitz et al., 2009, p. 83). There, patriotism and the possibility of taking arms against an oppressive government are closely intertwined. As a result, it is not surprising that the NRA’s insurrectionist argument and Second Amendment advocacy can be so popular in these states, in spite of their sparse recreational use of firearms.

Scholars have hypothesized about why Second Amendment advocates seem emotionally involved in the protection of gun ownership. Mencken and Froese established that American gun owners vary widely in the symbolic meaning they find in firearms; some associate gun ownership with moral and emotional empowerment and others do not (Mencken and Froese, 2019).

Lacombe demonstrated that gun owners are very politically active because there is a collective social identity tied to gun ownership and therefore they feel personally invested (2019). Dawson determined that, as the NRA has been increasingly using religious language to refer to gun ownership, to some gun owners, the Second Amendment became a right bestowed on them by God himself (Dawson, 2019).

The presence of this distinct cultural element is also consistent with a shift in firearm marketing and sales. Firearm advertising “moved from narrative—a description of how guns worked—to lyric—a description of how they made you feel” (Haag, 2016, p. 332). Melzer has described how former NRA president Charlton Heston strongly emphasized the idea of the gun as a symbol in the organization’s discourse: “Heston emphasized that a gun is more than a physical object, it is a symbol; that is, its importance lies in its representation of a particular American ideology” (Melzer, 2009, p. 121).

As Metzl puts it, “addressing guns symbolically means recognizing ways that firearms emerge as powerful symbols shaped by history, politics, geography, economy, media, and culture, as well as by actors such as gun manufacturers or lobbying groups” (Metzl, 2019, p. 2).

– Claire Boine, Michael Siegel, Craig Ross, Eric W. Fleegler and Ted Alcorn in What is gun culture? Cultural variations and trends across the United States