A TTAG Reader writes:

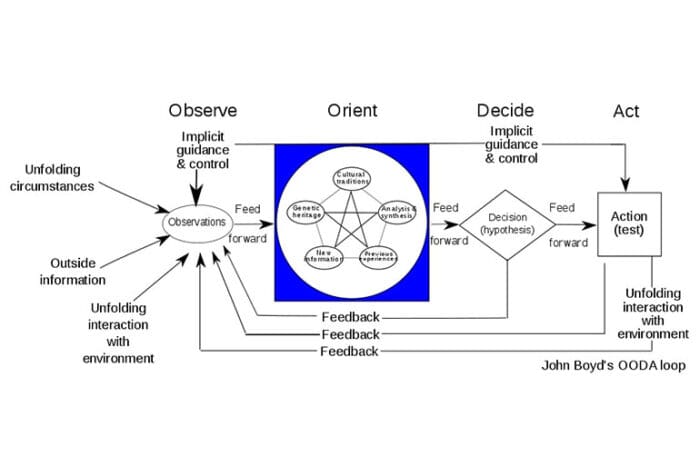

Innumerable articles have been written about the defensive use of firearms, especially handguns. Due to the high number of current and former combat veterans, much of the self-defense literary efforts seem to be influenced by small unit tactics. One of the significant theories of defensive tactics is the famous (infamous?) OODA loop.

Many gun owners who have had some personal defense training are familiar with the concept of the OODA loop. It seems to be almost as pervasive in application as the four rules of firearm safety. But is the underlying concept flawed when it comes to developing personal, practical abilities regarding the defensive use of guns?

The OODA concept apparently begins with the assumption that there are infinite threat scenarios which can confront an individual. But is that presumption proven or just assumed? If not, are we making a mistake relying on it?

Let’s Be Realistic

It isn’t really practical for an individual — the average gun owner — to train for and respond to an infinite universe of self-defense scenarios. In fact most self defense situations are encountered by people with no training at all. And there’s a fair amount of validity in the old 3-3-3 rule of thumb – most defensive gun uses take place within 3 yards, result in 3 shots fired, and last 3 seconds. In those situations, how much tactical training does the average person really need?

That raises another question: is the OODA loop even helpful? OODA (as promoted these days) appears to be based on the idea that preparation or pre-planning isn’t particularly useful, reasonable, or practical. That’s because of the almost infinite universe of possible threats. Any armed response will, by definition, be ad hoc requiring a heightened ability to observe, orient, decide and act. But what evidence — if any — do we have that pre-planning is pointless?

OK, that’s a lot of questions.

With the table set, let’s look at some “conventional wisdom.” We question the assumptions that OODA is the most effective means of responding to a threat, and that one should endeavor to be relatively skilled in the use of a firearm in “combat” situations.

A useful guide in the analysis is a long out-of-print pamphlet called Aerial Attack Study written in the 1960s. This guide is the seminal work of Air Force officer and fighter pilot John Boyd. Boyd, a Captain at the time, “wrote the book” on fighter tactics, unofficially and in his spare time. While it’s rooted in the capabilities of 1960 weapons and forces, the basics remain essentially unchanged.

Oh, and by the way, Boyd also invented the concept of the OODA loop.

In Boyd’s Aerial Attack Study, he analyzes air combat problems for fighters against bombers and fighters against other fighters. While the bulk of the pamphlet is narrative, there are mathematical supports for Boyd’s principles. He demonstrates how understanding the environment, analyzing the threat types, and learning successful tactics ahead of time are precursors to a successful OODA loop outcome.

Rather than accept the “infinite scenarios” theory of defense, Boyd shows the OODA loop isn’t actually an ad hoc tool, but the facilitator for employing decisions (or variations of decisions) that have already been established or planned. Boyd’s underlying conclusion is that the sphere of possible maneuvers or attacks can be defined, eliminating “infinite” possible scenarios.

Narrowing it Down

For the People of the Gun who contemplate defensive uses of firearms, the sphere of threats can also be defined, eliminating “infinite” possibilities that aren’t likely to confront the average person.

Given an individual’s habits, routines, and environment, a finite number of likely defensive situations can be identified. What that means is that the defender can reduce the number of possible threats to some very predictable avenues, and train for them. Given those limits, general principles of response can be imagined, analyzed, evaluated and addressed. That makes training and preparation much easier.

One might call this pre-planning. With pre-planning established (and always adjusted to account for weapons and mechanisms), one has an array of responses from which to choose. That’s where the OODA loop comes in.

Infinite Doesn’t Apply

Does this mean we really do need formal training in military type tactics? Not at all. How many defensive gun uses require much, if any pre-planning/OODA?” Research a decent number of self-defense shootings and ask yourself what were the limits of the situation (for both attacker and defender). What were the possible responses? Infinite doesn’t really apply.

Next, ask how much training the defender in these cases actually needed, how much and what type training did they have, if any, and did the training have any bearing on the outcome?

What we’re left with seems to be an uncomfortable lack of the definite. Pre-planning is very good for taking advantage of the principles of the OODA loop. Yet, if the vast majority of self-defense gun uses are near-instantaneous, happen at “contact range” and last only a few seconds, is there any support for the notion that planning, training, or OODA looping should take up much of our available time and attention?

On the one hand, I propose that preparation — pre-planning, thinking through scenarios and strategies — gives the defender a significant advantage. And training is never wasted. On the other hand, I can’t decisively assert that planning or training are significant factors in successfully defending oneself with a firearm for most people.

Planning and training vs. an ad hoc response. Is this just another version of caliber wars?