This article will, no doubt, upset many gun owners because it doesn’t immediately come out against so-called extreme risk protection orders and similar laws. The reasons for this are twofold.

First, opinions of new laws that have been issued in different states than my own and are already being implemented are irrelevant to the progress of that legislation; by default, it’s a peanut gallery situation if the movie isn’t playing in my own state; and,

Second, as someone who worked with attorneys for some years and has also done some work in the legislative process, what I know is that any new law is a “beta test.” That is, you really don’t know how it plays out until it’s actually in effect and has been in effect for some time. The reality is, you have to enact it to see how it works in practice.

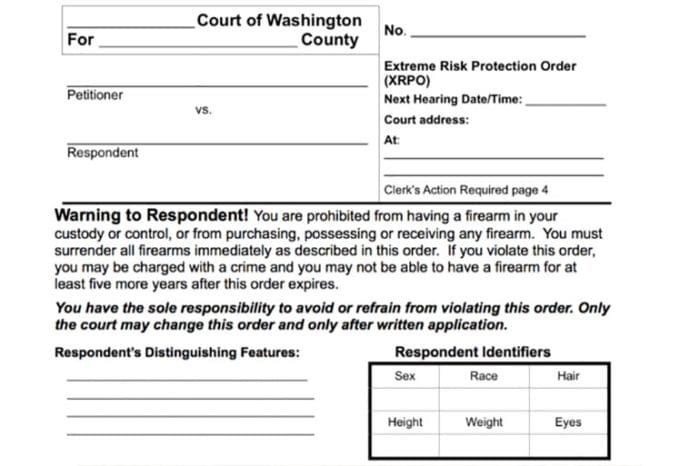

If such laws are correlated, after some time in effect, with a drop in gun violence in the states in which they are law, it’s likely we will see a push for more such laws, whether the drop in crime is directly related to the new law or not. This is why it seems important to contemplate the possibility of ERPO-like laws even in states that don’t have them yet.

Any state in which the voters feel there is a problem with “gun violence” could become a state in which those voters ask for and support such a law from their elected officials.

Each ERPO or “red flag” law is different depending on the state. It seems upon early review that, in general, the people who are allowed to request ERPOs are generally family members, law enforcement, and mental health workers. As a mental health worker myself, I am particularly curious about how such laws interface with HIPPA – the Health Information Patient Privacy Act.

While all health records are confidential, it’s also true in my state that I am mandated to report to law enforcement any person who I come to believe is a danger to themselves and others or any situation in which a vulnerable person such as a child or elder is being abused. No doubt this is the case in most or all states.

I suspect that most ERPO requests are likely to come from family members and law enforcement, if only because mental health treatment is mostly voluntary. If a person isn’t in voluntary mental health treatment, the mental health professionals will not know that the person exists.

I also think this is the case because family members, or law enforcement that have been called repeatedly about a particular person and visited that person, will likely have more direct knowledge of that person’s day-to-day and week-to-week life and activities. Even in regular therapy, a patient generally will see a mental health worker only once a week for about an hour, or someone who prescribes meds as seldom as once every one to three months. Also, a patient may simply never talk to a mental health worker about guns; it may not be relevant to the process of therapy or treatment that the patient is presenting for.

Here is the basic truth: Bringing a gun into a situation, whether it’s a low moment, a personal dispute, or a joke, greatly changes people’s perceptions of you for the most part, and not for the better. For my clients who own guns, particularly new gun owners, I tell them to leave guns and the mention of guns out of disputes because it’s pretty much always going to create mistrust and distancing and quite possibly the perception of the gun owner as a dangerous and threatening person.

I realize that responsible gun owners won’t like my saying this because it shouldn’t be that way. However, there is “should,” and there is the way it is. I recognize fully the right of gun owners to own guns for many other reasons than self defense, which is why I own guns, too. However, it’s also important to understand that the threat or actual production of a gun often escalates other people’s perception of a situation in a negative way. There is no way around that and it is an important consideration to keep in mind.

I am also aware that there are many good and responsible gun owners for whom the above paragraph might feel offensive. However, in the age of social media, it’s not uncommon to see people hiding behind keyboards making threats toward others and boasting about their capacity to harm others. While most of this might be BS, so to speak, it’s also a fact that many recent mass shooters made just such postings before actually committing those shootings.

As a result, it’s likely that things like online activity will be something that will be considered admissible “evidence” in ERPO requests. Anything that other people can see on a public platform is something that the end user, the poster, voluntarily put into the public space, so there is little ground to defend it as being unintentional. Most people have cameras that record video these days, as well, so disputes and such can easily be recorded and also used as evidence.

There is a serious question, for me, about the due process aspects of these laws and what type of evidence is considered admissible for the issuance of an ERPO. Of course, things like written materials, video, and visits from law enforcement are high on that list. One of my questions is whether verbal statements that are not backed by such evidence must be corroborated by another person or documented in some way.

Is it “word against word,” or is more proof required? The Maryland law, which I have been looking at, does not specify the evidence that must be presented, so this may be an area that remains to be seen as the implementation of the law progresses.

I am continuing to read and review ERPO laws and suggest you do, too. They’re becoming a reality in more and more states and it’s important to understand them better. I welcome discussion of them in the comments.