Rock Island Auctions‘ Seth Isaacson writes:

In the Pennsylvania countryside in the early 18th century, a uniquely American firearm was born that helped thirteen separate colonies defeat the greatest empire on Earth, form one nation, and span a continent. It is fitting that this new weapon was a conglomerate of ideas and built initially by German immigrants in the north and famously used by Anglo woodsmen in the south who became symbols of American ingenuity, self-sufficiency, and determination.

In the years following the Revolutionary War until the wide spread adoption of the percussion system, the long rifle reached its pinnacle in small shops in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Many are outstanding testaments to their skill and true pieces of Americana.

It is in this period that they earned their famous nickname from the men who famously used them: the long hunters who explored the Virginia backcountry known as Kentucky. Though they are more properly known as American long rifles, prior to the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson’s astounding victory over a superior force of British soldiers at New Orleans in 1815 solidified their nickname in our national memory. The song “The Hunters of Kentucky” about the battle contained the famous lines: “But Jackson he was wide awake, and wasn’t scared at trifles, For well he knew what aim we take with our Kentucky rifles.”

Those of you who attended or followed RIAC Auction undoubtedly have noticed the wide array of beautiful early American rifles. Many of these rifles came from the extensive Piedmont Collection. Our December Premiere contains another installment from this collection as well as rifles from other collectors. Many of these rifles were built by some of the most talented American artisans of the early republic. Their names are immediately recognizable by those who collect these pieces of art: John Armstrong, Jacob Dickert, Simon Lauck, John Moll, John Noll, John Rupp, George Schreyer, Frederick and Jacob Sell, Peter White, and many more. Each of these pieces is truly a masterpiece and several contain incredibly rare attributes.

The Kentucky’s roots came from two other firearms in the early 18th century: the shorter, larger caliber German Jaeger rifles brought from the Old World to the New by German immigrants and the long smoothbore fowling pieces and trade guns manufactured primarily in England and Western Europe and imported in large numbers for the fur trade.

Why exactly these two forms were married has continually been debated. What is clear is that fowling pieces and muskets were not well suited for taking game at considerable distances, and their larger bores meant they used a greater amount of lead and powder, which were more destructive to pelts and meat. This also meant that a hunter, be they Native or Euro-American, had to carry more weight in ammunition and had to get closer to their targets.

The Kentucky not only improved on those issues, but its long, rifled barrel also offered other advantages: the extended barrel combined with blade and notch sights provided a long sighting plane which allowed hunters to more fully utilize their rifle’s potential accuracy and also had the added benefit of providing more time for the slow burning black powder to combust and thus maximized power even while firing smaller, lighter balls. An experienced rifleman could hit a man or deer sized target reliably at 200 yards or more.

By the time unrest was growing in the colonies in the latter part of the 18th century, gunsmiths were producing a firearm that was found nowhere else in the world. Once the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, the American woodsman and his long rifle rose to the challenge. Many fought in local militias, but the Continental Congress also approved ten rifle units during the war including Daniel Morgan’s famous riflemen. They harassed British soldiers and targeted officers from outside effective musket range to remove key leaders from the battlefield and damage enemy morale. Morgan’s men later defeated the infamous Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of the Cowpens.

In 1780, the “over the mountain men bested a Loyalist militia armed with smoothbore muskets by picking them off at range at the Battle of Kings Mountain and turned the tide of the southern campaign against Lord Cornwallis. George Rogers Clark led a group of Kentucky militia and seized the isolated settlements in Illinois justifying the American’s claim to the vast swath of territory between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River.

At this stage, long rifles were still fairly plain and typically had wooden patch boxes, but his younger brother William carried a Golden Age rifle during his famous exploration of the Louisiana Purchase with Meriwether Lewis and the Corps of Discovery. Thus, while the majority of American soldiers during the Revolution were armed with smoothbore long arms, small groups of riflemen used their advanced weapons and prowess to make considerable contributions to the cause.

RIAC has auctioned beautiful examples such as a fine, silver inlaid rifle built by Simon Lauck. He and his brother Peter both fought with Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps and were gunsmiths in Winchester, Virginia after the war. It is a classic example of a rifle built during the Kentucky rifle’s Golden Age. Rifles from this era are favored by collectors due to the unique nature of each rifle and the variety of regional variations.

Aside from a few makers who preferred to focus on perfecting the nuances of their designs like John Armstrong, most used many variations of styles taught to them while apprenticed to a master. They in turn passed on their own variations on to the next generation of apprentices. This led to what we now think of as the “schools” based roughly in Lehigh Valley, Lancaster, York, Lebanon, Chambersburg, and may other locales based on shared attributes and lineages.

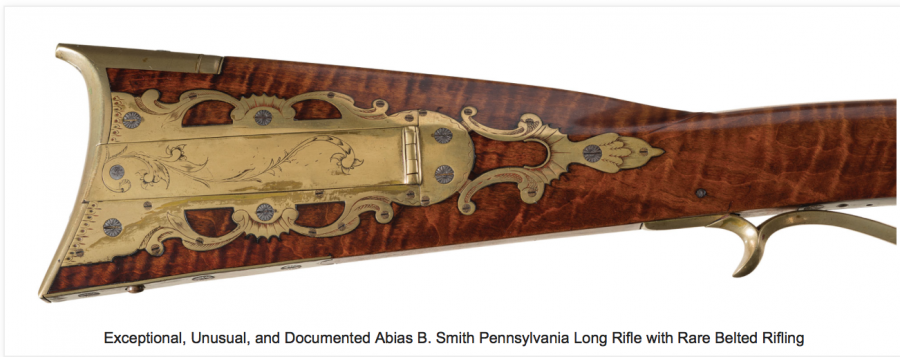

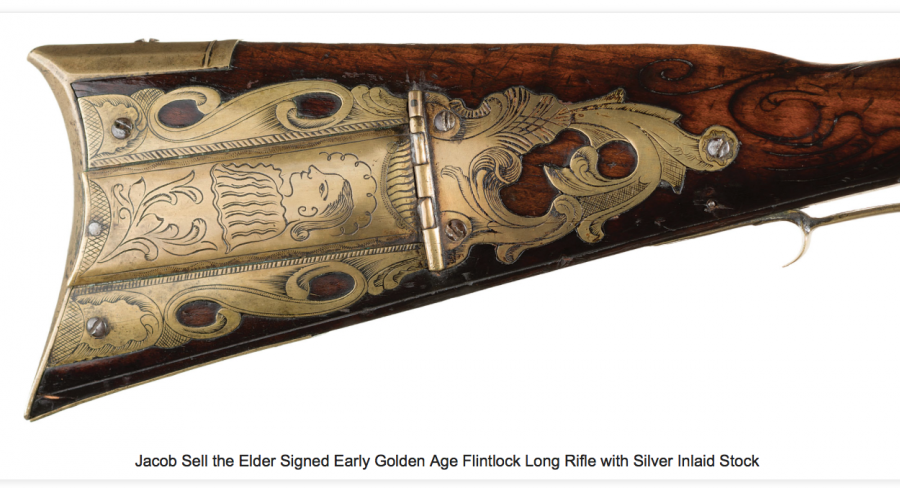

Gunmakers were influenced by one another especially in specific areas but also adapted art forms from Europe. The carving and patch boxes, for instance, follow European trends in terms of rococo and baroque scrolls. Note the incredible variety in patch box designs on these rifles and all the little details in carving, inlays, and little components. While there were tremendous variations, also note the consistencies such as the fixed blade and notch sights and the beautiful, full length, curly maple stocks.

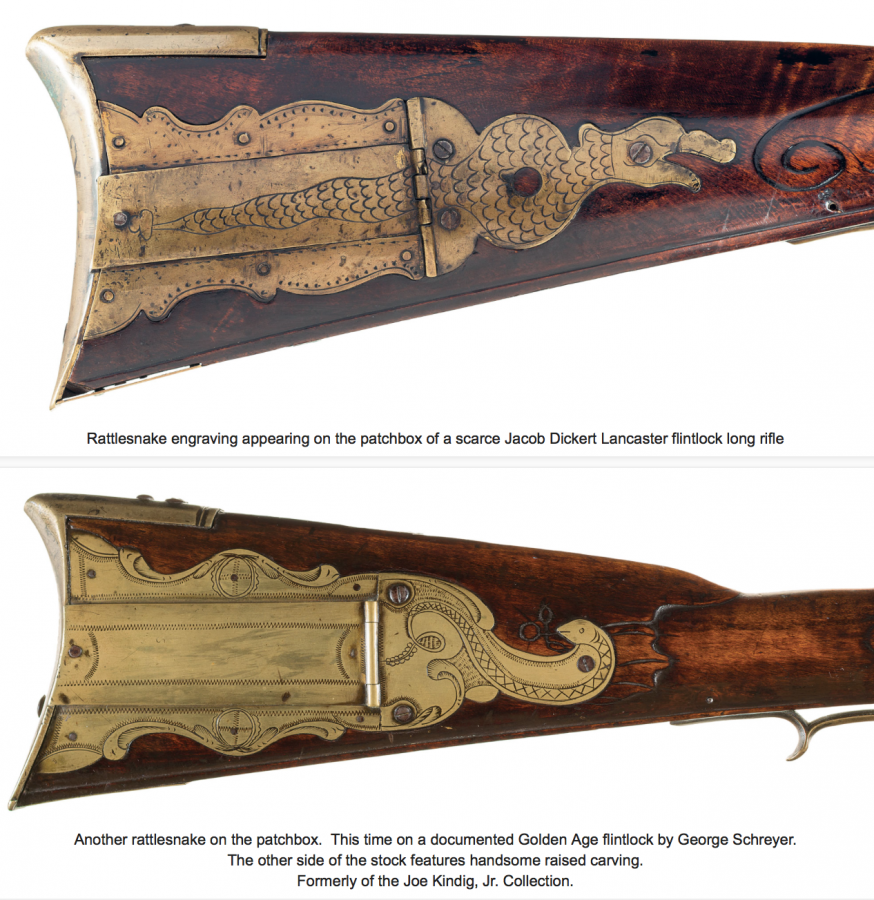

One area of variation among individual rifles is the variety of inlays. Many included patriotic motifs such as eagles and some contain important, but largely long forgotten, revolutionary era symbols. Such is the case with the rare rattlesnake designs on the Jacob Dickert and George Schreyer rifles. Like the long rifle itself, the use of the rattlesnake as a symbol of the American ethos well pre-dates the idea of a separate American nation. In fact, one of the first known uses of the symbol was in Benjamin Franklin’s famous “Join or Die” cartoon from 1754 calling upon the colonies to unite, with the support of Great Britain, to defeat the French in the Seven Years War (French and Indian War), a conflict started in part by a young British officer by the name of George Washington. Franklin’s cartoon came to represent the need for unity among the colonies in the American Revolution as well.

Rattlesnakes are only found in the Americas and were numerous in many parts of the colonies. Though they do not attack unprovoked, rattlesnakes defend themselves with deadly force when they need to defend themselves. This was the image the Founding Fathers wanted to present to the world in Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. Americans were not breaking from England needlessly; they were defending themselves against attacks on their lives and freedoms. Rattlesnakes also had another attribute that 18th century Americans knew well. As “American Guesser” wrote in 1775:

‘Tis curious and amazing to observe how distinct and independent of each other the rattles of this animal are, and yet how firmly they are united together, so as never to be separated but by breaking them to pieces. One of those rattles singly, is incapable of producing sound, but the ringing of thirteen together, is sufficient to alarm the boldest man living.”

Though this symbol was very important in the colonial era and for the young American republic, very few rifles have been found that incorporate the design, especially as boldly as these two examples by Dickert and Schreyer. The snake patch box designs of course relate to the Gadsden Flag and First Navy Jack used during the war, and Dickert’s is also similar to the design utilized on early Virginia Manufactory rifles.

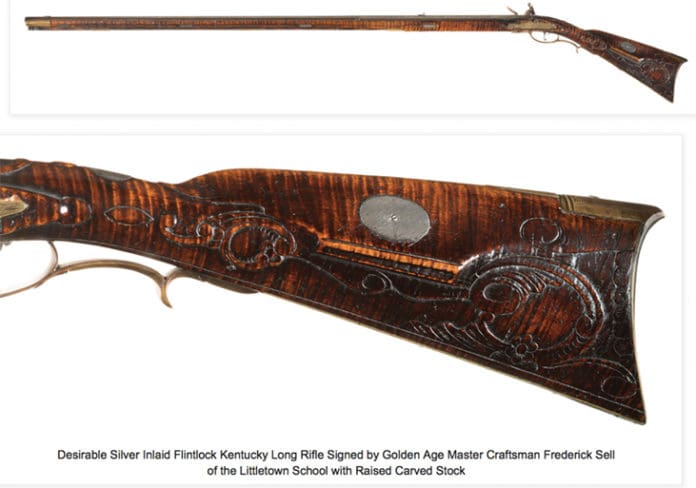

The Frederick Sell rifle is another good example of the paradox of both unity in overall design through the use of consistent motifs and basic configurations and yet the individuality of the combination of carving and engraving on each rifle. Sell was considered by influential Kentucky rifle scholar Joe Kindig, Jr. as “one of the great masters of Kentucky rifle making” and was part of one of the most influential gunsmithing families during the Golden Age. His greatness comes from the fact that he developed his tremendous skill set while working underneath at least three earlier accomplished masters: George Eister, John Lechner, and Adam Ernst.

His presumed father, Jacob Sell, was among the most talented makers of the prior generation, and Frederick’s brother who was also named Jacob (often referred to as Jacob the Younger) was also a gifted maker in his own right. Sell adopted the best aspects of the designs of each of the men under whom he worked. Thus, he created his own style and his own variations while keeping his designs tied to the past and reflected the American ideal of balancing community with individualism.

Peter White is also a great example of someone who was part of a family line of gunmakers that pre-dates the United States and continued well after our independence was secured by victory in the War of 1812. He is the son of either Nicholas or John White who were both gunsmiths during the fight for independence, and at least one of his sons continued to build rifles after his death in 1834. One of the interesting aspects of White’s rifle is that the lock appears to have been built by him. Most gunmakers used locks imported from Europe or produced by dedicated lockmakers in the cities. This rifle is also noticeably slender relative to others of the style and era.

By the time of White’s death, the long rifle and the flintlock system had peaked and were beginning to be replaced by shorter, larger bore rifles. The percussion system and the spread of industry also helped shift firearms production away from individually built masterpieces. The Hawken brothers’ “Plains” or “Mountain” rifle style relatively quickly became the preferred design as the frontier pushed ever further past the Mississippi.

Nonetheless, the long rifle persisted, and its legacy continued to influence American firearms for generations. In fact, long rifles have been in essentially continuous production by American gunmakers from the early 18th century into the present day. One look at the Contemporary Long Rifle Association is all it takes to attest the fact that the art of building the first truly American firearm by hand is still alive and will be for generations to come.

This discussion has hardly scratched the surface Kentucky rifle history. For more information see AmericanLongrifles.org,

KentuckyRifleFoundation.org, or the many detailed books including Joe Kindig, Jr.’s classic Thoughts on The Kentucky Rifle in It’s Golden Age and Merrill Lindsay’s The Kentucky Rifle.

Fascinating.

Thanx for posting.

I am still kicking myself for letting a bargain priced Remington 1816 Commemorative Flintlock skate by. Such rifles are a pleasure just to look at.

Great article!

Good history lesson with very good photos.

A Happy and Respectful Fourth of July to TTAG and readers.

Love the curly maple! Had a few pieces of curly maple furniture over the years as an antique dealer. Now some troglodyte would paint it!

Breaking: Several reportedly SHOT at Highland Park,ILLannoy July 4th parade. Highland Park is not known for gangs(but is anti-second amendment).

Do you guys have red flag laws? I’ve been told by presumably serious people that’s what we need to stop shootings like this from happening. Also, do you have permit/licensing requirements to carry a firearm in public? We don’t have either here, yet we have safe parades. Weird, huh?

I watched the local fireworks show last night. It was the first one since 2019 due to Covid insanity. The crowd was about 15-20% of the pre-Covid crowd. It felt odd.

Happy independence Day, Montana, from the northern colonies. Stand strong, stay Free. Always. Cheers.

@R/S

Thank you. Apologies for forgetting to wish you the same on 01 July.

No worries buddy, we aren’t celebrating it this year anyways 😉. Maybe next year, or the one after… (but thanks Montana).

Gasp! “Ghost Guns” in today’s anti-gun definition.

A serial serial number requirement is an invention of the 20th century. The Gin Control Act of 1968 (GCA68) mandated that ALL firearms manufactured after that date have serial numbers.

I’ve long had my eye on one of those Hawken rifle kits. Thinking about finally making one.

.40 cal,

“the Gin Control Act”???? OH NOES!!!! Don’t tell me those Leftist/fascist idiots are trying to bring back Prohibition!!! OTOH, they are stupid enough. Legalize pot, and make booze illegal (again). Makes at least as much sense as anything else those morons do.

A little know trivia… the representatives had been drinking gin when they presentd the bill

Lol

Actually its a typo… Gun not Gin

The second pic down, of the muzzle –

Was that bore ‘keyed’ to a special projectile?

…and, I don’t see any serial numbers, and I *really* doubt the owner went through a ‘background check’ or several days wait to take delivery on that fine specimen.

And he likely made his own black powder from the dirt in the pen or the stalls of his horse, cow, or other farm animals…

Looks like it was made with twin-groove rifling to use a girdled projectile. The Brunswick rifle that replaced the Baker in British service was made in the same way.

The contribution of rifles to the cause of the American Revolution is quite overstated. George Washington disliked rifles as a significant part of the army and, generally, the men who carried them. The siege of Boston highlights the friction between Washington and the frontier men who brought rifles — a number of them deserted to the British after a series of clashes with the chain of command. Daniel Morgan wrote that riflemen were basically useless without proper troops to back them up…All this also ignores that American loyalists carried rifles in equal numbers to their rebellious counterparts (see the number of rifles confiscated after Saratoga, and in the area after the battle of Moore’s Creek; some historians posit that the word “rifle” was used to mean all sorts of arms, but I tend to doubt that, people knew the difference between a rifle and a musket). The German Jaeger troops generally outclassed American riflemen because they combined marksmanship with military discipline, the latter being lacking among American riflemen. German riflemen drubbed their American counterparts at Flatbush and a dozen other skirmishes . The British produced a pattern of military rifle that was farmed out to dragoons, light infantry companies, and loyalists that was arguably a superior military rifle than the type used by the colonists…The British had ready access to “superfine” Swiss and German powder, the Americans generally did not, which is one theory as to why American rifles were long, to allow more burn time for crappy powder. The bores of rifles rotted out quickly as well, degrading accuracy (and explaining why one german officer noted that American rifleman took “a quarter of an hour to load”, anyone who had tried to load a crusty rusty muzzleloading rifle can understand.) The caliber was also generally quite large on American rifles of Revolutionary vintage, the same as the German rifles they were based on — .60-.69 was not uncommon, smaller caliber rifles came later. After the French and Indian War, the British had a superior light infantry doctrine, making much better use of Native Americans as well.

This isn’t to rain on everybody’s parade here on our Independence Day, it’s to point out how a persistent myth in fact undermines a far more striking reality. The British weren’t bumbling fools. larger than life heroes in buckskin didn’t coolly pick off a laughable enemy from afar. There wasnt an easy way out of colony status. The British had better troops, better doctrine, better supplies and logistics, etc. we won by holding out long enough to drill an army in the European model, that was properly armed and equipped, that could take the British on directly. How did we hold out long enough for that to happen? It doesn’t make much sense…The grace of God?

GOD yes but we had a lot of help from the French…it helped that the British were arrogant & had an inept insane king(sound familiar?).

But in spite of all you posted….we still won the American Revolution. I have ancestors that fought in it. And we should never forget or deny that God himself had HIS great hand in our winning it.

LONG LIVE THE REPUBLIC AND MAY GOD CONTINUE TO BLESS AMERICA.

Here’s wishing everyone here (including Miner49er and Dacian) a HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY.

A persistent fact undermines an insidious self-serving anti-gun agenda for control of the population and turning the constitution into a ‘permission’ they grant and control or remove as they see fit … that fact is pretty much the bill of rights and more specifically explained in relation to guns and other rights in the Bruen decision.

Sounds like Washington who owned rifles and pistols somehow dislikes rifles and the citizens who carried them, red coats and everyone else was better but somehow by the grace of God America Won. Perhaps instead of popping firecrackers today we should sit down and sip tea?

Indians joining forces with red coats clearly shows those Indians were completely clueless about who they were in camp with. They went from bad to what would become 1000 times worse had red coats prevailed.

As for German superior marksmen it’s a wonder Americans did not starve from an inability to hunt game, etc. Reality was in those days hunting was a daily survival ritual as was gutting and cleaning your kill. Such skills are transferable.

With God’s help America won because red coats did not possess the will to win. I don’t suspect red coats want a rematch…do you?

I think most of my points went over your head, but I’ll address a couple of yours nonetheless,

*Sounds like Washington who owned rifles and pistols somehow dislikes rifles and the citizens who carried them, red coats and everyone else*

Washington had great respect for the culture of frontiersmen — despite being a societal elite of the Virginia gentleman-farmer class, he was close to being a frontiersman himself — he had made numerous expeditions to the frontier, not just in the course of military service, but to claim land for himself in the Ohio country. As a gentleman and military officer, however, he had little patience for the refusal of the men from western Virginia, western Maryland, and Pennsylvania to hew to the line of military discipline. Hence he limited the numbers of riflemen in the CA.

*Indians joining forces with red coats clearly shows those Indians were completely clueless about who they were in camp with. They went from bad to what would become 1000 times worse had red coats prevailed.*

This is totally false. The British had set the boundary to prevent colonists from encroaching on Indian land west of the Allegheny’s because the British government, fresh off the F&I War, had no interest in spending the money and troops needed to administer and secure further western settlements, and to fight the Indians. The American colonists needed room to expand — there are interesting accounts of sons of prominent families in Concord, Massachusetts leaving for the west…There just wasn’t enough farmland left in the original colonies. For the Indians, allying with the British was the sensible thing to do.

*As for German superior marksmen it’s a wonder Americans did not starve from an inability to hunt game, etc. Reality was in those days hunting was a daily survival ritual as was gutting and cleaning your kill. Such skills are transferable.*

This is another bit of fantasy. The average farmer or mechanick didn’t spend a lot of time hunting and, except in the westernmost regions or in remote areas, didn’t rely on game to survive. On the frontier it was a different story, but that doesn’t mean everyone was a skilled hunter. There are accounts of forts that lived due to the game brought in by just a couple hardy hunters, they being the only ones who could slip through Indian cordons around settlements. There were few weapons and less powder — I can’t recall if it was written Colonel Zane or someone else, but a letter was sent back to the continental administrators begging for powder, there being only 14 pounds existing in the several forts of certain area. I can easily burn a pound of powder in an afternoon of shooting a musket, and our powder is better — I use 100 grains for a shot give or take, whereas the standard charge for a Brown Bess was IIRC 230 grains. German Jagers were both professional gamesmen and trained riflemen, and ruthlessly efficient soldiers, the backbone of their prince’s armies. There are hessian accounts of how the Jagers would encamp in the hills surrounding the rank and file German troops to pick off deserters. They certainly were a dangerous adversary.

*With God’s help America won because red coats did not possess the will to win. I don’t suspect red coats want a rematch…do you?*

Fewer than 1 in 100 of Britain’s available military served in North America. The British public was very divided, and records in the House of Lords shows members excoriating their government for sending “wretched hirelings” from Germany and Russia (the Brits originally tried to contract an army from Russia as well as the German principalities) to subdue the free sons of Englishmen. I don’t know about the redcoats, but the British public and government did not have the will to win.

Washington won the revolution by surviving. He suffered many defeats but each time he got the bulk of his army away from the loss. The French did help. But none of their help would have mattered if Washington has surrendered himself and his men after a defeat.

He outlasted his enemies desire to defeat him. Sound familiar?

You are indeed correct. The British had a far superior army and a global empire and were not only masters at sea and ground but also logistics.

We won the same way countries have bested us in recent times. Washington employed a Fabian strategy which he borrowed from the Roman general of the same name who fought Hannibal. Guerrilla warfare was an important aspect but it wasn’t the sole defining aspect of the war that allot of people think it was. The continental army still had to prove itself in the field and it took a long time for that to happen, and as great of a general as Washington was, he wasn’t perfect, and had to be talked into not launching a massive (and likely fatal) assault on New York, and instead head south to Yorktown.

Frances biggest contribution was defeating the Royal Navy at sea. That set the stage for Yorktown to be what it was.

Yorktown proved to the British the war simply wasn’t worth it anymore, and that the Americans were getting their shit together. The French naval victory and French and Spanish threats to the rest of their empire forced them to realize further prolonging the war would likely lead to great loses globally.

“Frances biggest contribution was defeating the Royal Navy at sea”

That was a non-trivial action. Prevented England from sending and landing reinforcements. However, England fought 7 other wars during the American Revolution (civil war 1.0). The period wasn’t just England against American colonists:

Anglo-Spanish War : 1775-1783

Anglo-French War : 1775-1783

Fourth Anglo-Dutch War : 1780

First Anglo-Maratha War : 1775-1782 (British v.s Maratha Empire)

Armada of 1779 : (British v.s Spanish and French) Failed Invasion of Britain, caused catastrophic defeat for Spanish and French… To assist American Revolution.

2nd Anglo-Mysore War : 1779-1784 (Britain and Allies v.s Kingdom of Mysore)

Fourth Anglo-Dutch War : 1780–1784 (British v.s Dutch Republic and French) British gain large amounts of Territory and Trading rights.

Indeed. Things could have easily gone a different way under different circumstances. Happy Independence Day, Sam. May you see many more and may it never change. Cheers from the northern colonies 😉.

That was a great article and appropriate. I’ve wanted a long rifle since the first time I saw Fess Parker as Daniel Boone. Time to get busy. It will be a re-pop as I will shoot it. Guess what the motif on the patch box will be.

I have a .50 cal muzzleloader rifle manufactured by Thompson-Center. I have had other percussion cap rifles however this is the perfect rifle for muzzleloader hunting. In my state we are not allowed inline percussion rifles for hunting the muzzle loader season. I wish I could find another short barrel length .50. I shoot the sabot .45 caliber 300 grain hollow point (with plastic cover). Unbeleivable accuracy from a muzzleloader. What is great is that Muzzleloader regulations require no backround check to buy a muzzleloader kit. So much fun and pride to build, Bluing your own barrel and finishing your own stock.

Great piece iof history but like an awful lot of other firearms of the period the decorations displayed were just another example of FASHION over FUNCTION. I rather doubt that any real hunter or combat soldiere would have had such highly decorated pieces. Too easy to damage and too expensive. To me, the real collectors piece is the one that’s been used for real. The workmen’s tool in other words

Albert…. in case you missed it…this is an American holiday used to, basically, commerate us kicking British tyranny butts out. You know, the same basic feudal tyranny your country has lived under since its inception and still does today in its modern day form.

Go find your own holiday and stop trying to breath freedom vicariously by getting into our country holidays and business.

sir albert of nuttingham…you are so wise and sophisticated. Me being a dumb American I’d grab a rifle like that and use it to swat a fly, stir paint, etc. Shucks…Now I know better.

The attitude among many historians is that the highly directed pieces that have survived have indeed done so because they were primarily show pieces rather than working pieces. The article does touch on wood patch boxes as being the norm on earlier pieces, in essence a note that many guns were not highly decorated.

On the hand, I own an original Brown Bess, the penultimate military workhouse long arm, and while it is plain in comparison to some surviving rifles and certainly has no extraneous brass, the wood moldings around the lock and sideplate and down the stock are more elegant than they absolutely need to be. The ramrod pipes aren’t plain brass rings, but slightly stylized. Nothing that would add significant cost or time to production, but no totally plain either. I think the attitude of the period allowed for such unnecessary elegant touches at the expense of absolute brutalist efficiency, just as today, even the simplest car has some degree of styling even if it doesn’t need to.

The British Pattern 1776 military rifle, used extensively in the AWI, is likewise plain in comparison to these brass mounted rifles, but retains some of the elegance of a British sporting rifle of the time.

Prince Albert, this something your ilk will never understand. Style and personalization of a firearm is important. After all, the weapon you choose to defend your life is pretty personal. Something else for you on the anniversary of our independence from your colonial rule. We kicked your ass. Twice. Then we saved it. Twice. Albert, you need to sit down and shut up until it’s time to dial 911 again.

Princess Albert….You mean in your dreams like a real working firearm……like non of you English fuzz balls are allowed to own.

Sheer beauty. Thanks for posting!

Watch a Master Gunsmith handcraft a Rifle of this era, (it runs almost an hour,, but every minute is a fascinating showcase of skill using period methods and implements) Happy 4th!

Somehow, I doubt the early colonists used hacksaws to make their firearms… 🙂

Near the end, the video mentions ‘caliber’. Each barrel was hand-made, so the gun smith made a custom bullet-mold for each rifle.

It was claimed that the number of custom bullets that weighed one pound determined that rifle’s caliber.

So, when did caliber change to a percentage of an inch?

The Kentucky rifle. Industrial Hemp cultivation. State level Energy Independence Drilling and refining. Constitutional carry. I love this Commonwealth.

And the longest kill shot of a British general during the Revolutionary War. Nearly 300 yards with a Kentucky long rifle.

It was the Kentucky/Pennsylvania long rifle that got me started as a collector. The lines, craftsmanship, and artistic value, as well as the mechanics and design caught my interest. 1 of my most prized pieces in my collection is a fairly plain, working man’s Lancaster type Long Rifle. Beautiful in it’s simplicity with just enough embellishment to be just a bit more than just another gun. A wonderful piece of curly Maple, and slightly understated scrollwork on the brass patch box. The rifle has been verified as authentic and dates to around 1760-1770.

Since the bullet mold was long gone, and most rifles of the time had a mold fitted to the individual rifle bore, nothing standard in size back then, I did have to have a mold made to fit.

I picked it up as a young GI stationed at FT. Campbell KY. way back when.

Today, while it hangs above the fireplace on display, I do take it down and shoot it a couple times a year. I would not be afraid to hunt with it were it necessary. The old lady will still hit a 4 inch bulls eye at 200 yards, and possibly longer range. I just don’t want to load heavy and possibly damage her. Besides, I have a repro as a common shooter in .45 cal. Always liked the old flintlocks. Powder can be made if needs be, flints, or agates are available for the finding once you learn what to look for and where. Lead can be cast. Do that with a modern rifle.

10-4 ON GREAT ARTICLE ..

WONDER WHAT A 22LR OR 22 MAG SINGLE SHOT NEW UPGRADE WOULD LOOK , BE LIKE .. JUST A THOUGHT … UUUM BOLT ACTION WITH CLIP .. ??

“…the added benefit of providing more time for the slow burning black powder to combust…”

Wait a minute, I always thought black powder burned really fast, and smokeless powder burned slow. And I swear I read this on TTAG many years ago. Am I incorrect here?

Also for anyone that shoots a flintlock I’d appreciate recommendations on some. I’ve always wanted a flintlock of some kind, either a Kentucky/Pennsylvania long rifle or even a Brown Bess style musket.

Not all black powder burns fast.

The finer the powder grind, the faster the burn rate, because more of the surface area is exposed to the flame…

Good to know. Thanks.

Black power burns at a given rate no matter the pressure. The rate is determined by the proportions of the mixture and the size of the granules but primarily by the size of the granules. The size of the granules … the larger the granule the slower the burn rate and the smaller the granule the faster the burn rate. So, not all black powders burns at a fast rate and not all black powers burn at a slow rate – it depends on the size of the granules.

The rate of smokeless burn is primarily determined by the pressure, the more pressure the faster it burns and the less pressure the slower it burns.

Although both have an ‘explosive quality’ – black powder is an explosive and smokeless powder is a propellant.

The big effectual difference between the smokeless propellant factor and the black powder explosive factor is that the smokeless propellant factor has a much greater duration of pressure with a significantly lower loading rate and the black powder explosive factor doesn’t.

There’s a fundamental confusion by many shooters about the nature of black powder and smokeless powder.

Let’s start with the basics: Black powder is a low explosive (something like C4 is a ‘high’ explosive, and these ‘high’ and ‘low’ ratings have to do with the speed of the shock wave coming off the explosion). Black powder, heaped up in a pile outside of a gun, tends to have the same rapid, but relatively fixed, burning rate, and it burns fast enough to cause a true explosion (supersonic shock wave). Smokeless powder, piled up outside of a gun, burns not in an explosive manner, but rather in a deflagration, a rapid, but sub-sonic burning that occurs layer by layer.

Let’s put them into cartridges and put them into guns. Now the game changes. Black powder is still an explosive – it explodes behind the projectile, but black powder’s burning characteristic is pretty much fixed. If you have a black powder muzzle-stuffing pistol, you can load 20 grains or 200 grains of FFFg and all you get is more smoke and a bigger “bang.”

Try that with smokeless powder and you’ll be in the ER in a hurry. Smokeless powder’s burning characteristics, when confined, change dramatically. Smokeless powder burns faster the more pressure you put on it, and the more powder you add, the more pressure you produce, and the more pressure you produce, the faster it burns, and the faster it burns, the higher the peak pressure. This means that as you add more smokeless powder to the load, the higher your peak pressures will go, and they go up on a non-linear curve – which means that small changes in the amount of smokeless can results in guns disassembling themselves on the firing line.

The surface area of powders changes the burning characteristics – in both types of powder, smaller particles result in faster burn rates. Smokeless powders are produced in a wide variety of particle shapes and with a number of different coatings to control the burn rate.

Now you might understand why the Sharps rifles chased ever-larger black powder charges in their rifles – but ultimately, didn’t end up getting the velocities they wanted until smokeless showed up.

Long story short: 1. The ultimate pressure reached in black powder guns is NOWHERE close to the maximum pressured reached in smokeless powder loads. 2. The pressure of black powder loads is much less sensitive to the amount of powder, whereas a relatively modest increase in the quantity of smokeless powder can cause rapid firearm self-disassembly.

Good information. Truly appreciate such an in depth answer.

This is how I remember the ttag comment section: as a source of knowledge along with everything else. Thanks for the informative post, DG. Miss them.

Interesting article. But, note the drop in that stock. Bet, the muzzle really jumps, smacks one’s cheek…..

That is a European influence in gunstock design. You can see something similar in European hunting rifles with their “hogback” style buttstocks to this day. Please see the following for comparisons:

https://www.merkel-die-jagd.de/en/products/stocks/wood-stocks/

Not at all. Consider the rifle was designed to be fired standing and broadside to the target. Recoil is quite minimal. My kids fired .45-.50 caliber flinters in grade school.

@Rider/Shooter

“Happy Independence Day, Sam.”

Thanx for the acknowledgement, eh?

It was earned. Undoubtedly by you yourself and most certainly by your Founders and their compatriots. Would that our early history was so meaningful.

Needs more Picatinny.

I think the admin of this website is genuinely working hard for his web page, as

here every data is quality based information.

I have read so many articles or reviews on the topic of the blogger