By Peter Schechter

My collecting interest is the “battle rifle” which means, to me, a magazine-fed “semi-automatic-only” rifle that was actually issued to troops, regardless of its ammunition. Battle rifles occupy a fairly short-lived period of infantry warfare history between the nearly universal pre-World War II use of bolt action rifles and the 1950’s-onward global domination of selective fire rifles brought on by the remarkably durable design of Mikhail Kalashnikov’s AK-47.

One of the first semi-automatic-only rifles with a detachable magazine ever used in international warfare, however, was the Winchester Model 1907 Self Loading (S.L.) rifle. In fact, it was used in battle decades before World War II, and not by the United States.

A simple blow-back action rifle shooting a unique medium power cartridge that was never intended to serve as a military combat weapon, the Model 1907 S.L. enjoyed decades of success and popularity with hunters, law enforcement, and penitentiary security forces in the United States and elsewhere. But it was also the first battle rifle used by the British in World War I, and it wasn’t used by ground troops.

A few specially modified Winchester Model 1907 S.L. rifles were used in the very earliest days of air combat by aircrews of “flying machines” or “aeroplanes” of Britain’s new Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which in 1918 was merged with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) to become the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Semi-automatic rifles were also initially used by German aircrews of “Flugzeug” of the newly created Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches, or Imperial German Flying Corps, also called the Luftstreitkräfte (which disbanded in 1920 according to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles).

According to most historians, the first-ever air combat occurred just eleven years or so after the Wright Brothers’ famous December 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk. Here’s how it happened — more or less — at least in terms of the weapons used.

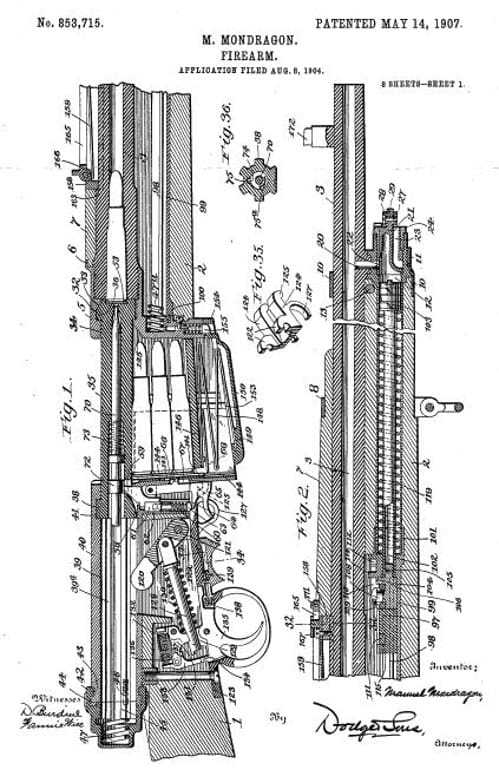

Early 20th Century events in Mexico played a significant role in the first British-German air-to-air combat through a circuitous chain of events. In August 1904, Mexican gun designer Manuel Mondragón filed an application for a United States patent on his new semi-automatic rifle invention. U.S. Patent Number 853,715 was granted to him on May 14, 1907.

The patented design was adopted by the Mexican Army in 1908 as Fusil Porfirio Díaz Sistema Mondragón Modelo 1908 (M1908). Because no Mexican firearms manufacturer could produce Mondragón’s rifle at that time, Mexico contracted with the Swiss company Schweizerische Industrie Gesellschaft (SIG) for production of four thousand M1908 rifles.

By 1910 only about 400 rifles had been delivered by SIG to Mexico, and the Mexican Army didn’t like what they had ordered. The rifle’s inability to cope with poor quality Mexican-made 7x57mm Mauser ammunition, and its intolerance for sandy environments, plus the high per-rifle cost charged by SIG, led the Mexican government in 1910 to cancel the remainder of the order.

That left SIG with an inventory of at least several hundred, perhaps even a couple of thousand, completed, but undelivered Mondragón M1908 rifles, and more in various states of completion.

The M1908 made by SIG was actually a great rifle, even if intolerant of sand and poor quality ammunition. Mondragón’s semi-automatic action design was decades ahead of its time.

It had a gas-operated cylinder and piston arrangement to drive the bolt carrier, and a rotating bolt engaging helical lugs in the barrel block to go into battery. Cleverly, the bolt could be disengaged from the gas system, and the rifle then operated as a straight-pull bolt action rifle.

It had a non-detachable box magazine with ten-round capacity that was charged using two five-round stripper clips, and it came equipped with a bipod and a bayonet. However, conventional military doctrine at the time disfavored rapid-fire infantry rifles, as commanders believed that soldiers would simply “waste” ammunition if they could fire their weapons faster.

Even the M1903 Springfield bolt action rifle had a switch preventing soldiers from reloading cartridges from the fixed box magazine with each cycle of the bolt handle.

The Outbreak of War

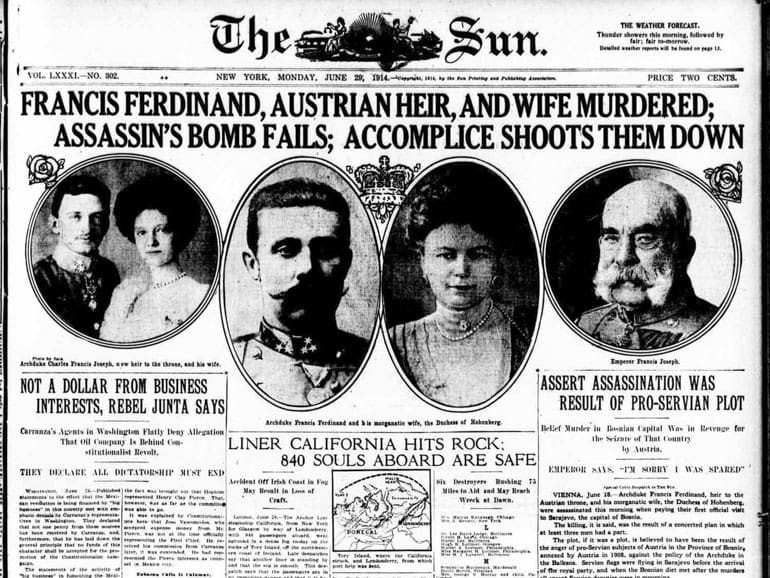

Soon after Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, World War I broke out across Europe. The Imperial German Army (like all European military services) looked for weapons wherever they could be found, and the Germans learned of SIG’s undelivered inventory of as many as 3,600 Mondragón M1908 rifles.

The rifles were tested by the Germans for infantry use, but were found to be just as intolerant of trench mud and dirt as they were of sand regardless of ammunition quality, and their use by German infantry troops was rejected.

Meanwhile, by late 1914, all combatants began sending “flying machines” over enemy territory for reconnaissance and observation purposes. Merely flying these “aeroplanes,” as they were starting to be called, made of thin strips of wood, wire, and canvas, was dangerous enough, at first. Pilots on all sides of the conflict were adventurers and gentlemen, and they initially waved their honorable greetings as they flew past each other.

Very quickly, however, the pilots and observers (in 2-seaters) started shooting at each other with sidearms with the goal of preventing the targeted aircrews from delivering their gathered intelligence (including photographs of armament columns and troop formations). Such pistol and revolver fire had very little practical effect.

As thoroughly described and illustrated in Harry Woodman’s book “Early Aircraft Armament – The Aeroplane and the Gun up to 1918”, all combatants were scrambling to mount light machine guns on aircraft as soon as they possibly could.

However, in early 1914 even the lightest machine guns were too heavy to be carried aloft without seriously compromising the aeroplanes’ basic abilities to actually get off the ground, climb, maneuver, and stay aloft. And then there was the problem of the propeller, which initially precluded any thought of fuselage-mounted, forward-aiming, machine guns.

The Germans knew of a few thousand otherwise useless Mondragón M1908 rifles in SIG’s inventory. Where could they be used by troops in a clean environment? The answer was obvious: there’s no mud in a flying machine.

Germany bought SIG’s entire remaining inventory and the Imperial German Flying Corps adopted the Mondragón M1908 rifle, issuing two of them per aircraft crew. The rifle was modified to accept a 30-round drum magazine and was designated as the Fl.-S.-K. 15 (Flieger-Selbstladekarabiner, Modell 1915 – Aviator’s Selfloading Carbine, Model 1915).

While German, French, and British engineers were working as fast as they could to figure out how to mount machine guns on aeroplanes, the German flyers immediately started shooting at British planes, pilots, and observers with the much greater firepower provided by their modified Mondragón M1908 rifles.

The RFC aircrews had no domestically produced answer, but a few British military officers were familiar with the commercially available Winchester Model 1907 S.L. rifle chambered for the fairly powerful and unique .351 Win SL round. Twenty grains of smokeless powder pushed a 180 grain jacketed lead bullet at about 1400 fps to deliver a punch of about 785 ft-lbs of muzzle energy, this being nearly identical to the ballistic performance of today’s Buffalo Bore .357 Magnum 180 grain hard cast gas check ammunition (LFN-GC).

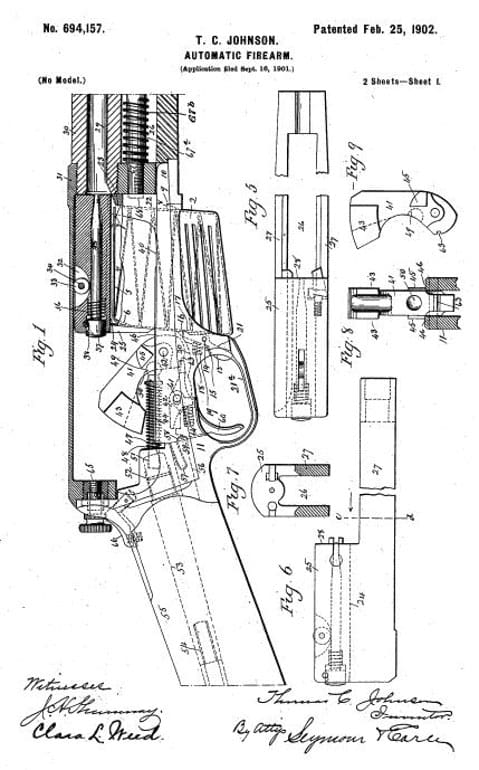

The history of the RFC’s Model 1907 S.L. rifle began in 1902, when Winchester Repeating Arms (WRA) firearms designer Thomas C. Johnson patented the blow-back semi-automatic action that would later be used by WRA in its Model 1905, 1907, and 1910 S.L. rifles.

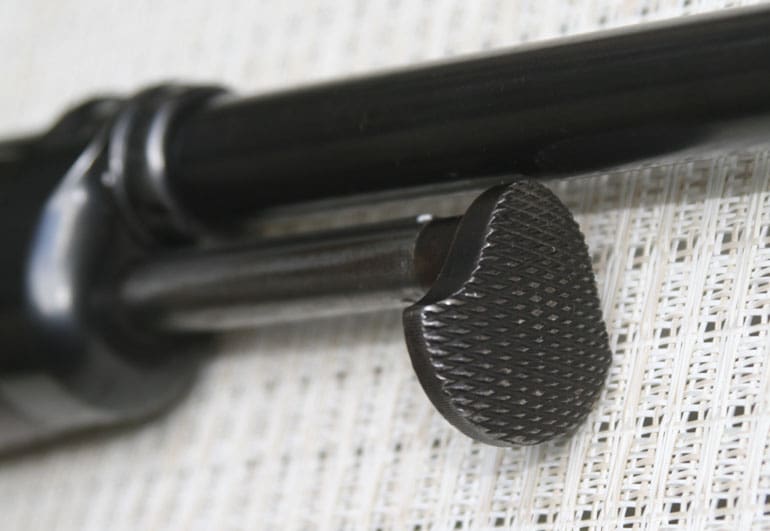

In late 1914, the British contacted WRA and asked T.C. Johnson to create a modified Model 1907 S.L. rifle that could be operated by RFC aircrews wearing heavily padded cold weather flight suits and gloves. The requested modifications included an oversized charging handle, an enlarged trigger guard, an enlarged magazine release button, an extended 15-round magazine (rather than the standard 5 or 10), and a case catcher to prevent ejected spent brass from damaging the delicate parts of the aeroplane.

Johnson himself worked on the requested modifications, according to A.O. Edwards’ book “British Secondary Small Arms 1914-1919: Part 2, RFC and RNAS Small Arms” (Solo Publications, Canterbury, Kent, UK, 2005). The Winchester Arms Collection housed at the Cody Firearms Museum includes what are almost certainly two of Johnson’s RFC-prototype Winchester Model 1907s, Serial Numbers 20355 and 16482, with differing versions of the requested modifications.

Both prototype rifles have enlarged charging handles and trigger guards, but the modifications differ in their details. Both rifles are equipped with canvas brass catchers, but again the construction details of the bags and their mounting schemes are different.

While T.C. Johnson almost certainly sent a design for the requested modifications to England, it appears that neither prototype at the Cody Firearms Museum embodies exactly the final design that the Royal Flying Corps actually received.

The RFC obtained from WRA, through London Armoury Co., Ltd., 120 commercially available Model 1907 S.L. rifles in seven shipments from December 17, 1914 through April 12, 1916.

At that time, all firearms imported into England were required by English law to be re-proofed by either the London or Birmingham proof houses, and marked in some way as being “not of domestic manufacture.”

After the rifles were received in London and re-proofed, some of the 120 rifles – the exact number is not known – were modified as requested by the Royal Flying Corps according to T.C. Johnson’s design, either by a British government armory (possibly the nearby Royal Small Arms Factory Enfield) or by one or more available and capable London gun makers. I know of no existing records that would indicate exactly where the modification work was done, or by whom.

Seventy-eight thousand rounds of commercial .351 Win SL jacketed lead core ammunition was also purchased. As there was no domestic production of this ammunition in England, and that purchase represented only 650 rounds for each purchased rifle, it seems clear enough that only short-term interim use of the Model 1907 S.L. rifle was ever contemplated.

There are a few historical hints and suggestions that some of the purchased commercial ammunition was modified to shoot incendiary or tracer rounds, for the dual purposes of allowing the shooter to see where he was shooting and to possibly set the wood-and-canvas enemy aircraft on fire. While there is no doubt that the British were developing incendiary rifle projectiles at that time, to my knowledge there are no known written records proving that an incendiary .351 Win SL round was ever created, tested, or used in combat.

The RFC modifications are seen in the following photos.

Additionally, two small holes were made in the left side of the receiver, the precise purpose or function of which is not known. There are no known surviving examples of the brass catcher designed to fit on the mounting lug of this rifle, but it is presumed that the holes were part of the mounting scheme for the canvas bag.

Some unknown number of the modified Model 1907 S.L. rifles were actually used by RFC aircrews, though there are no known surviving written records of that operational use. A number of the rifles were almost certainly lost with their aeroplanes and crews throughout 1915 into the first half of 1916.

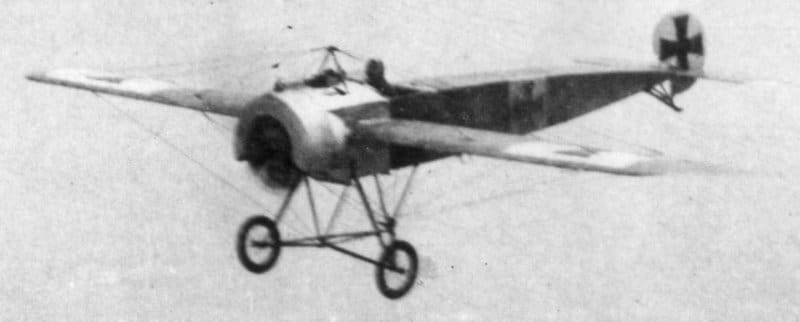

When the Germans figured out how to time the firing of a machine gun so that bullets would pass through the propeller arc without striking the blades, and then mounted a forward-directed machine gun in front of the pilot, Luftstreitkräfte use of their modified Mondragón M1908 rifles came to an abrupt end.

The Fokker Eindecker was the first truly successful “fighter plane” with a forward-facing engine cowl-mounted machine gun, and it ushered in a period of German air superiority in 1915 known as The Fokker Scourge. The British response was to develop and deploy “pusher” planes, in which both the engine and propeller were behind the pilot rather than in front of him, thus allowing an unobstructed machine gun to be mounted in or on the nose of the plane.

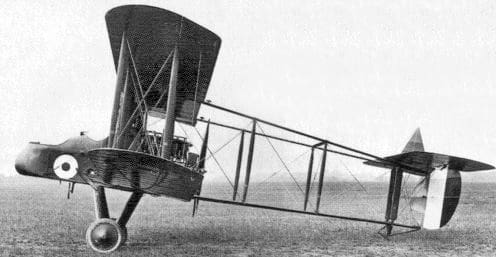

The first British combat pusher aeroplane was the F.E.2b, but that machine did not arrive at the Western Front until very late 1915. Throughout 1915, British aircraft losses were high and increasing, as the German pilots were improving their tactics and gaining more air combat experience.

Some RFC aircrews probably continued to take their modified Winchester Model 1907 S.L. rifles into the skies through late fall and winter of 1915, and even into early 1916 until sufficient numbers of F.E.2b aeroplanes, with their far more effective firepower in the form of a forward-mounted Lewis gun, entered service.

The F.E.2b more than held its own against the Fokker Eindecker in air combat, and when joined in January 1916 by Britain’s new single-seat Airco DH.2 pusher plane (which also had a forward-facing Lewis gun mounted in front of the pilot), the tide in the skies turned in favor of the British, at least at that stage of the war — before much more advanced combat fighter and bomber aircraft started to enter service on both sides.

British engineers finally figured out the machine gun synchronization gear in spring 1916 and the first British fighter plane so equipped was the Sopwith 1½ Strutter, which entered service in May 1916. By then, however, the Fokker Scourge had already been squelched by Britain’s pusher planes. No more RFC-modified Winchester Model 1907 S.L. rifles were taken aloft.

What’s left of the armament from the dawn of aerial combat? Not much. While hundreds of thousands of Mondragón M1908 rifles were eventually produced in Mexico and used by military services around the world, only an exceedingly small number of German Fl.-S.-K. 15 air service versions survived The Great War, disarmament under the Treaty of Versailles, and World War II.

For its part, the Model 1907 S.L. rifle was one of Winchester’s longest-produced rifles in the company’s history, with production finally ending in about 1957. To the best of my knowledge, however, only two London-proofed RFC-modified Winchester Model 1907 S.L. rifles are known to exist today.

Because the RFC-modified Model 1907 S.L. rifle and the German Fl.-S.-K. 15 are the first “battle rifles” used by opposing forces in international warfare, albeit in “flying machines” over European battlefields in 1914-1916, they deserve a place in my collection. One now has it, and I doubt I’ll ever even see, let alone own, the other.

Well, the war was supposed to be over by Christmas…

Seems to be a common refrain in the annals of war.

Great article! Let’s see more of this and less of redundant articles on ARs.

Compelling story of the race to kill the enemy in the sky! Honestly war is responsible for much of our “advancement”😄

Love this article! A fascinating look at some amazing machines — both guns and planes — that I hadn’t seen before.

Keep these coming.

Fascinating article! Thank you for writing and sharing this.

Thank you.

Cool historical article. I love these pieces.

Awesome article! I love how the details of the design and the history of the time come together to form a compelling story. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you, Mr. Schechter. A fascinating and thorough study of a facet of early air warfare that I knew nothing about. Please write more.

Outstanding. Thank you!

Outstanding article. Very nice work!

C&Rsenal have an episode on the Winchester 1907. It would be interesting to see if they do an episode on the Mondragon rifle.

NOTE from the author: I wrote “While hundreds of thousands of Mondragón M1908 rifles were eventually produced in Mexico and used by military services around the world, …” I don’t think this is correct; in fact, I’m nearly certain that the only Mondragon M1908 rifles ever produced are those 4000 made by SIG around 1910. The web page https://www.militaryfactory.com/smallarms/detail.asp?smallarms_id=455 says that “local Mexican production” continued until 1943, and that users included another dozen countries in addition to Mexico and Germany. This information appears to be incorrect. The web page https://mondragonrifle.com/history/ indicates that all of the following are erroneous statements: “over a million made,” “they were made in Mexico,” and “they were used in both World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam.” The same website suggests the possible source of the mistaken information, as well. My apology for propagating the misinformation.

Great read.

Very cool piece of history. Neat article, TTAG needs more of the genre

The holes on the left side of the receiver may have been there to mount a lanyard or cable. No one would fly with an unsecured weapon.

Note from the author: From a close inspection of T.C. Johnson’s prototypes at Cody Firearms Museum, I have a good educated guess as to the function of the holes, or at least the larger of the two holes, on the left side of the receiver. The brass catcher was constructed from a canvas bag attached to a steel frame that covered the ejection port, and most likely extended up, across the top, and down the left side of the receiver. Given the shape of the mounting lug, the user would slide the frame from the butt end of the gun forward into position. When fully on the lug as far forward as it could go, there was probably a thumbscrew/pin or other sort of movable detent on the left side of the frame that would mate up with the larger hole, locking the whole frame and bag in place on the rifle. Worse than taking an unsecured rifle up in an aeroplane would be dropping a full bag of spent brass or having it fly off while in flight. There is not evidence that the any of the long guns taken aloft by the Brits, Germans, or French were in any way attached to the planes — until machine guns were firmly so attached.

The men who flew those early flying “contraptions” certainly were confident… those proto-planes had more in common with my wicker lawn chairs that an airplane!

Thank you for the history write up, always loved the WSL rifles.

Probably why those early planes were nicknamed “kites”.

More. Of.this.

Less.of.politics

Even less of everyday carry. Jeez it’s 3 times a day some days.

Interesting stuff. Recently been looking into antique semi autos. I think the Remington 81 in 300 Savage is the top of my list.