by Beetle ([email protected])

“If it ain’t a Savage, it’s a Substitute!”

“The Savage 1911, defending America for 100 years!”

If these two phrases sound a bit off to you, it’s for good reason. Typically these phrases are spoken in regards to Colt and John Moses Browning’s timeless 1911 pistol design. However, in 1911 a relatively new and small arms manufacturer nearly won the contract for what would become America’s most iconic sidearm . . .

Arthur Savage & The Savage Arms Company

Arthur Savage was born in 1857 in Jamaica. Much of his youth was spent traveling the world trying to find his calling. At age 17 he traveled to Australia and lived among the aborigines. He also did a stint as a sheep shearer and later a doctor’s assistant. After leaving Australia, Savage lived briefly in London, and then moved again to New York. In 1886 he went to work for a publisher of scientific papers. This seemed to stimulate his creative mind and he soon invented a fiber cleaning machine used to make rope, for which he received a patent.

In 1883 the British government announced that it wanted a repeating rifle based on the Martini action. Savage began work on his design in 1886 and submitted a design in 1887. He received a patent for his design, but it was not selected by the British government who instead went with the Lee bolt action.

Savage moved his family to Utica New York and continued work on refining his design. It eventually morphed into a rifle that was tested by the US Army in 1892. While the Army did not select his design, Savage was convinced that he could produce a rifle to compete with the likes of Remington and Winchester. In 1894 he launched the “Savage Repeating Arms Company” and started production of the Savage Model 1895 lever-action rifle. It was a commercial success. Savage sold approximately 5,000 rifles over a four year run.

In 1899 Savage renamed the company to simply “Savage Arms.” He updated the Model 1895 rifle, and the Model 1899 was launched. One novel aspect of the Model 1899 rifle was that it used a rotary magazine. This magazine allowed the Savage rifle to be one of the first rifles to accommodate spitzer bullets (most modern rifle bullets today are of the spitzer design, where the tip is a point instead of a round nose). Competing rifle designs at the time were mostly based on a tubular magazine, which are not well suited for spitzer bullets where the point of the bullet could ignite the primer of the round in front of it.

The Savage Model 1899 went on to be one of the most popular firearms ever made, with production lasting well into the 1980s.

The .38 Service Revolver in the Moro Rebellion

Around the same time that Savage Arms was selling the Model 1899, the United States had to put down a rebellion in the Philippine Islands (which it had won from Spain in the Spanish-American war). At the time most of the troops were equipped with the Colt double action revolver chambered in .38 long colt. Feedback from the troops was immediate; the revolver lacked sufficient “stopping power” against the Moro Tribesmen. The troops reported that the tribesmen could be hit multiple times but continue to fight. Based on this experience the United States was convinced that it wanted an automatic pistol and it wanted it in .45 caliber.

Elbert Searle and the Trials of the Century

In my last article about the Borchardt C93, I described how the invention of smokeless powder sparked a flurry of new pistol designs. Two such designs were patented by Elbert Searle, an independent inventor working out of a small machine shop in Philadelphia. We are not sure how Elbert was introduced to Savage Arms, but in 1905 the company purchased the rights to his designs.

In 1906 the U.S. Army sent out notice that it would be conducting tests to find the next service pistol. A number of arms manufacturers responded, including Colt, DWM (Deustche Waffen Munitions), Webley, Grant-Hammond, and Savage. Of the original proposals only the Colt, DWM, and Savage designs were deemed mature enough for further testing.

Searle moved his workshop from Philadelphia into the Savage factory in Utica to refine and actually build his design. Fortunately for Savage the tests were delayed until 1907, giving Searle and Savage time to complete the work. The army tested the Savage pistol by firing 913 rounds through the new (and probably hand built) weapon. Overall the army was pleased with this first effort and it could see the possibilities with the automatic pistol. The one thing that the Army did note with the Savage was harsh recoil. We will come back to this later.

The army put in an order for 200 pistols that incorporated some requested design changes. The army also made similar requests of Colt and DWM. Colt readily agreed and submitted a price of $25 per pistol. At this point Georg Luger felt that he was being set up by the Army who was destined to pick an American pistol, and declined the offer to make 200 pistols (a big part of this is probably because the costs involved to tool up and make .45 acp parts were significant and would not be recovered with “just” 200 pistols).

Remarkably, Savage also declined the offer for much of the same reason. It did not have the resources to produce 200 pistols without incurring a loss. However, some back room discussions must have taken place and the US government was willing to pay a whopping $65 per pistol — nearly 3X the price of the Colt. Savage saw this as an opportunity to have the government fund both the tooling necessary for the .45 pistol as well as tooling for a smaller version of the same pistol that they had planned for commercial release.

Unfortunately Savage had some bad luck with these pistols. 5 pistols disappeared on their way from the Savage factory to Springfield Armory. Once the pistols arrived in Springfield, the Army immediately rejected the entire lot because Savage did not mark the “safe” and “fire” markings onto the frame. Then an additional 67 pistols disappeared on the way back to Savage. Thus Savage not only had to remark the frames, but they had to manufacture another 72 pistols to make up for the “missing” ones. Today the acknowledged total of Savage .45 pistols manufactured is 288 (200 original, 72 replacements, and 16 prototypes).

The pistol I have is one of the 288 pistols that were built for the test trials. Let’s take a closer look at the gun. In the following picture you can see where Savage had to rework the gun to mark “Safe” and “Fire”. Also note that the grip safety is open at the top. The Army would later criticize the design as debris could find its way between the safety and the frame, preventing disengagement of the safety.

The magazine release is quite an interesting design. It’s built into the front strap of the grip. It’s actually a pretty nice design, allowing for activation from either the pinky or ring finger of the gripping hand. The magazine itself is one of the earliest known uses of a double stack — kinda. The magazine is tapered and wider at the bottom where the rounds kinda-sorta double stack, or at least slightly stagger. This allows the Savage to fit 8 rounds in the magazine vs. 7 in the Colt.

Field Strip

To field strip the pistol, first the slide is retracted and the thumb safety is put on “safe,” which also serves as a slide lock. Note, the slide is VERY DIFFICULT to rack!

Next the rear assembly is rotated 90 degrees clockwise…

…at which point the entire firing group can be removed. Note the piece of metal that also comes loose. This metal serves as the rear sight and as the extractor. When a round is chambered it cams this metal up slightly, which is then visible on top of the slide. Yes, a loaded chamber indicator circa 1907!

Here you can see how the trigger activates a lever on the firing group.

Theory of Operation and Mechanics

Searle described his pistol as a “locked breech delayed blowback” design. This is in contrast to Browning’s locked breech short-recoil design. Let’s examine this for a bit. Most handguns fall into one of two camps: direct blowback and locked breech (note: I am again simplifying in order to keep the discussion at a high level). Direct blowback is the simpler design of the two. In a direct blowback gun, the gases from firing directly push against the slide, which causes it to open the breech, eject the spent casing, and load the next round. The issue with direct blowback is that powerful cartridges produce too much gas and can cause the slide to move before pressures have dropped to safe levels. It is generally acknowledged that direct blowback is unsuitable for calibers greater than .32ACP/.380 Auto. In order to make direct blowback work with larger calibers, a combination of very stiff springs and/or heavy slide is needed to slow the process down so that the slide doesn’t open too early. In addition, recoil can be harsh with direct blowback guns and large calibers.

In contrast, Browning’s design is recoil operated. In this design, it’s not the exploding gases which act upon the slide, but the recoil generated from the bullet launching forward. This is Newton’s 3rd law of motion: “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” The bullet launching forward causes the slide to move backwards. In the Browning design, the slide and the barrel both move backwards momentarily before the barrel swing link causes the barrel to unlock from the slide and tilt downwards. The net result of this action is that much of the recoil is absorbed by the weight of the slide and barrel moving backwards as well as the tilting action of the barrel. The disadvantage of this design is that accuracy is more difficult to achieve because the barrel moves both horizontally (moving backwards and forwards) and vertically (swinging up and down).

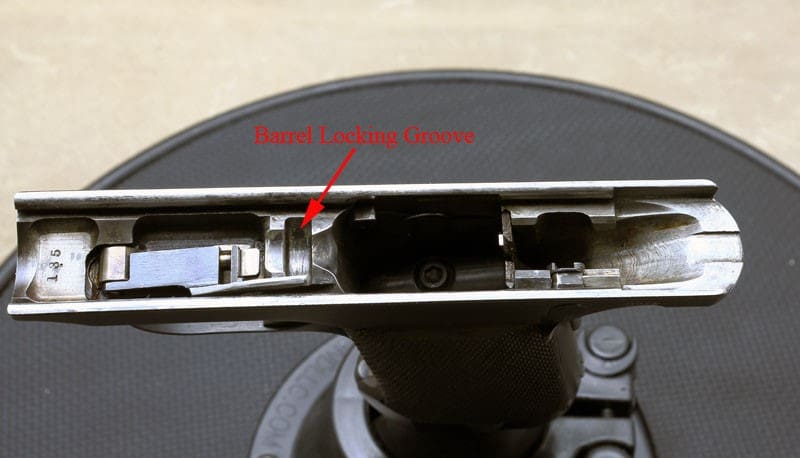

Searle thought his design was unique in that it was a delayed blowback mechanism. As you can see from this picture, the barrel itself has two lugs on the top and bottom. The top lug rides in a channel cut into the top of the inside of the slide. The bottom lug holds the barrel and prevents it from moving forward or backward.

In the first photo, you can see the angle in the channel cut into the slide. As the slide is blown backwards, this angle causes the barrel lug to twist, unlocking the breech for cartridge ejection. In theory this setup should be extremely accurate, as the barrel has essentially no horizontal or vertical movement. It just rotates in place.

What would stop this action from happening almost immediately before the bullet has left the chamber? Searle called this a “delayed blowback” design, because he had the barrel rifled in the opposite direction that the barrel would rotate in. His thought was that the mass of the bullet being spun in the opposite direction would delay the rotation of the barrel and the unlocking of the breech.

We now know that this theory doesn’t really work. In reality the rotation of the barrel and unlocking of the breech was nearly instantaneous with the bullet firing. Fortunately there is just enough delay where case ruptures don’t occur. The Savage .45 pistol is essentially a direct blowback gun. Hence the repeated comments about the harsh recoil of the pistol. In fact, one of the field testers stated “I’d rather fire 2,000 rounds from the Colt than 500 from the Savage.”

Field Testing

The Army took the 400 pistols (200 Colt and 200 Savage) and issued them to various troops for field testing. The feedback from the troops was not very positive for either gun. It is speculated that the average soldier was not yet ready to accept an “automatic” gun in place of a revolver. For the savage, chief complaints included high/excessive recoil, a grip safety that could trap dirt, difficulty in racking the slide, and difficult to use ergonomics.

Colt took his feedback and completely redesigned his entry into what would eventually become the 1911 that we all know. Savage lacked the resources to do a full redesign, so they were only able to incorporate a few small changes. In November of 1910, the Army again tested the two competitors by firing 1,000 rounds. The Army reported that neither design was fully ready, but that the Colt was “much more satisfactory.” The Army requested that each company take one last try at refining the design for a final test.

The Final Test

On March 15, 1911 the public was invited to view the “shoot off” between the Colt and Savage designs. Both Arthur Savage and John Moses Browning were in attendance. The first 1,000 rounds went fine for both pistols. However, the Savage’s heavy recoil took a toll on the internal parts. When the smoke had cleared, the Colt had fired 6,000 rounds without issue while the Savage had 31 malfunctions and 5 parts breakages.

The decision was clear and the Army picked the John Moses Browning design to be the military’s service pistol, designated as the Model of 1911, or M1911.

The French Pick the Savage Pistol in .32

While Savage did not win the US Army contract, it did nevertheless go on to sell a large number of pistols based on the Searle design. If you recall they charged the government $65 a pistol to “tool up.” In addition to tooling up for the .45 pistol, they also used those funds to tool up for a smaller version in .32. The smaller version went on to sell in big numbers. In fact, Savage even won a contract to supply the French army in WW1. Over 44,000 .32 pistols were sold in just a couple of years both domestically and abroad.

The JMB/Colt 1911 Pokes Arthur Savage in the Eye One Last Time

Whether it was the loss in the US Military trials or some other reason, Arthur Savage left the company he founded. He moved out to California where he had his hand in a variety of ventures including citrus growing, tires, and oil wells. However it could be said that making guns was in his blood. He decided to start a new arms company with his son, now called “AJ Savage” (Arthur Junior).

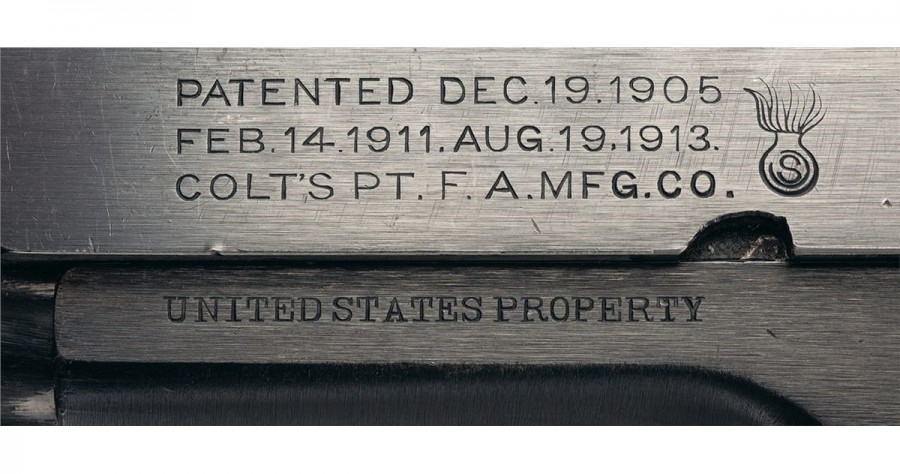

Savage used his contacts with the military to secure an order to make none other than his nemesis, the M1911. He spent much of his fortune to get the new factory set up, including the needed machinery and tooling. The first step was to make working slides and have them tested for interoperability. He sent a few to Springfield Armory. Savage 1911 slides can be identified by the flaming bomb and “S” symbols.

Unfortunately before he could go on to make full pistols the war had ended and all contracts were cancelled. Because he never produced a functioning pistol, the government refused to make payment. The JMB/Colt 1911 had done it to him again!

Arthur Savage died in 1938. The pistols that bear his name ended up being a commercial success and even supported the allied troops in WWI. However, the Savage 1907 .45 pistol will forever be a footnote in gun history as the gun that almost became the M1911.

About the author: Beetle is an amateur collector, writer, and photographer. His favorite FFL had this to say to him: “you like all the weird stuff.” Beetle can be contacted through the following web forum which he is trying to help a friend launch the Vintage 1911s forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

Superb write-up. I’ve always been intrigued by the Savage, and have come “this close” to bidding on a .32 and the similar-looking Astra 600. You have a beauty in your collection and a real piece of history.

Well done. This is great.

Great read and there’s some fascinating history in there. Good work!

Leave it to the French to choose a .32 when both .38 and .45 are available.

Why carry all the extra weight, if all you intend to do is surrender.

Touché

M. JaxD, pour le gagnant.

.32 auto was in service with military and police units world wide at that time in history. I remeber when West German .32 Walther PP’s were sold surplus in this country for 199 bucks each. Included the full flap issue holster the cops wore their side arm in. That was about 1980.

Very, very interesting stuff, thanks.

This is the kind of stuff I love reading about – it combines history AND guns! What could be better?

I have enjoyed reading the posts on the Thompson, BAR and now the Savage 45. I hope we have more articles like this and less politics.

+1

I would much rather read stories like this than read about the latest rant from a liberal goon. This was a fantastic stress reliever. Bravo!

I concur.

What REALLY would have been interesting is if somehow the Luger in .45 had been chosen. Now that would be crazy…

Would have been weird during the WW’s, that’s for sure.

The US would have probably made a “slightly different copy” of the Luger had it won so they can produce it without paying royalties like they did with a certain service rifle having a “Mauser-like” action. I don’t blame the Germans for being wary at this point.

Very good!

Thank you for the fine piece of history.

The US Army was seeking out and testing “self loading” handguns as early as 1899 or before, which is generally prior to the Moro Insurrection (although there had been sporadic fighting ever since the conclusion of the Spanish-American War in 1898).

The Moros probably amplified the Army’s desire for a powerful “auto” handgun, but the demand was already there.

I feel like TTAG is getting back to form. Between write ups like this and the gun reviews coming from Nick, I am loving the latest content.

Keep up the good work!

Yes. A lot of good stuff coming out on TTAG recently. Loving it.

I agree. These history pieces and Nick’s reviews are my two favorite parts of TTAG.

What a lovely piece of industrial art!

If you like Beetle’s write up here, we are proud to have Beetle as a very distinguished member over at Calguns.net His write ups about his trips to the Rock Island Auction every year in pursuit of very interesting and collectible guns are amongst the best posts I have ever read on the Internet.

You can read it, called “Chasing the Grail” here http://www.calguns.net/calgunforum/showthread.php?t=477248

I am a C&R fanatic and Beetle’s observations and point of view about the guns that are his passion are quite interesting, entertaining and just plain fun to read.

Enjoy,

Capy

Hi Capy,

We just might see beetle doing similar write-ups on TTAG here as well, if all goes to plan and folks enjoy seeing the content (and, from the comments, it sure does seem that’s the case).

Jeremy

Excellent article, nice to read a review that’s accurate and professional. I’ve owned a few of the 32 and 380 versions, they are very well put together and the ergonomics are great even though they look like they wouldn’t be.

You forgot to mention that Colt provided the ammo for the final shoot off and used a heavier projectile than the spec called for…

What’s that saying about finding yourself in a fair fight?

Hmmm, I’ve not heard this before. Originally a 200gr bullet was used, but the major ammo manufacturers (Frankford Arsenal, Union Metallic Arms, and Winchester) later agreed to a 230gr bullet. My understanding was that Frankford Arsenal provided the ammunition for the tests.

However, both Savage and Luger complained in the first round of testing about the quality of the ammunition. They both felt that the inconsistent ammunition caused their entries to perform poorly.

Excellent piece of writing on a gun that has held my interest for a long time. Sadly, I’ve not yet found a good example of the 1907 to add to my collection yet.

Great article. Object of desire for sure.

These are great! More please.

Lovely review. Thank you!

A beautiful piece of design and engineering with spectacular machine work, much like the Swiss Luger and higher end Mausers from a time when precision craftsmanship was an end in itself

So you are saying we could have had an even less reliable pistol for middle-age men and mall ninjas to fawn over and have delusions about?

I had an opportunity to handle one of these back in college when I volunteered for a campus museum. Wasn’t able to fire it, but did perform some basic maintenance on it for the display. A very awesome looking pistol and felt great.

Very good article. But I think that is one ugly handgun.

It looks very Buck Rodgers next to old slab sides, IMO. Would have been interesting to see what futuristic had looked like in the 50s if the savage had won.

Excellent work, presentation and research. I look forward to seeing more articles by this author here and elsewhere. Obviously not a “Johnny come lately” in the firearms world. Meticulous fact finding and presentation.

Great article!

I love your articles. Very interesting and entertaining.

Always good to read a fine article, thank you. Savage pistols seem popular with pulp fiction writers, a favourite genre of mine.

Very good info. Lucky me I came across your site by chance

(stumbleupon). I’ve saved it for later!

I blog frequently and I genuinely appreciate your information.

The article has really peaked my interest. I will take a note of your website and keep checking for new details about once per week.

I subscribed to your Feed as well.

It is interesting that Newton formulas do not support themselves through slow motion footage taken of recoil operated firearms. In theory, the barrel should have some backward motion at instant of bullet exit, but it does not occur excepting with a very little jerk. In fact, this does not hurt Mr. Newton’s respectability since an unnoticable motion relating his famous laws occurs within that time as being; nearly equal force affecting at both directions, back and forth. At instant of expelling the bullet outside the barrel, the projectile is a plug as soon as

remaining inside the barrel and excepting the gas leakage, the pushing force to back and forth is equal giving nearly no motion of reciprocally movable barrel and i