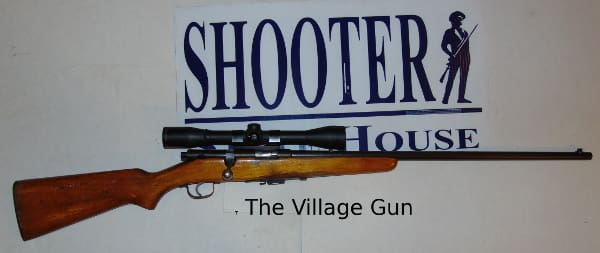

The Village Gun is my name for an old Springfield 84-C. My father acquired the rifle and a state of the art Weaver 3/4 inch straight tube scope for $7.50 during the Depression. In previous articles, I revealed my father used that the Village Gun and the neighbors for deer hunting. Please don’t grouse about another post about this storied firearm.

My father didn’t use the Village Gun primarily for deer hunting. A.22 rifle has dozens of uses for on a farm at the edge of wild country. Oer the roughly 60 years of its Wisconsin existence, The Village gun was used for most of them. One of those: hunting ruffed grouse.

It was illegal to hunt ruffed grouse with a rifle in Wisconsin. It’s one of those laws born from good intentions; it’s a bad idea to fire a rifle randomly into the air. A high-powered rifle, shot into the body of a grouse, results in a bloody, inedible mess. But a .22 rimfire rifle, used judiciously, can take grouse regularly and safely, and produce edible results. I know. I did a lot of it, even though it was technically illegal at the time.

Hunting grouse with a .22 takes more skill than hunting them with a shotgun. A good dog helps immensely. Where grouse have not been hunted hard, a dog is just another four-legged predator. My dog and I hunted as a team. A Labrador, he was a natural hunter and retriever. He would range ahead, find a grouse, and tree it. My job was to creep up and shoot it. It’s common for a grouse to fly into a nearby tree and sit there, confident of its invulnerability to the predator on the ground.

My dog quickly taught his boy that he barked differently for grouse or squirrels. His barking would lead me to the spot, even in dense cover. Grouse had to be approached with more care than squirrels. Knowing what you are looking for makes them easier to spot. A good dog will quickly retrieve a grouse knocked to the ground, and bring the bird to you. The hard part: seeing the grouse within rifle range before they fly away. People have shot grouse on the fly, with a rifle, but I’m not one of them. I don’t recommend it.

The grouse above is fairly typical. When they’re on the alert, they hold their head high, the neck stretched up. I took this picture in January; the feathers are fluffed up. When you’re dressing out your first couple of grouse, examine them closely to understand their anatomy. It will help in knowing where to aim.

I learned that a .22 does not spoil much meat, even if the grouse is shot through the breast. The point of a folded wing is a good aiming spot, as is a little below the base of the neck from any angle. Head shots make for better bragging rights, but the base of the neck is an easier target. I would not use hyper velocity .22 cartridges for this sort of hunting. Standard velocity is enough, and quieter.

Truth be told, I’ve missed a fair number of grouse. Fortunately, a .22 in the woods is relatively quiet. The grouse often fell on the second shot.

Pick a hole between the twigs and branches; it’s surprising how much a twig can deflect a bullet. When you’re shooting at a small target, hitting a twig means a probable miss. A scope makes it easier to miss twigs and branches that can be masked by iron sights.

If you’re hunting with a rifle and shooting into the air, you need to know the country and the direction you are shooting. You don’t want to accidentally shoot someone or break a neighbor’s window. It doesn’t apply only to grouse. Squirrels are shot out of trees as well. When I hunted grouse with the Village Gun, I knew where the neighbors’ houses were, and how far a bullet would travel. Quick digression . . .

The warnings on today’s .22 LR boxes say the bullet can travel a mile-and-a-half. That’s under optimum conditions with a lot of safety factor thrown in. It’s very hard to get a .22 LR to travel more than a mile. At the end of the mile, a .22 LR bullet will be traveling at about 200- 240 feet per second. It could put your eye out, but is unlikely to be fatal. For common .22 LR ammo, a mile is the max range. At angles higher than 35 degrees, the range decreases. Fired at higher angles, the terminal velocity will likely be less than 200 fps.

I didn’t know any of that when I was 12. I knew a bit about trajectories from firing countless pebbles from slingshots. The .22 cartridge box said one mile, so I was careful to avoid shooting in the air toward neighbors’ houses. It was easy. There were only three within a mile, all of them on one side of the Namekagon River, South of where I lived. So all shots aimed toward Northeast or around the compass, toward North, or West, toward South were good.

I remember the first grouse I shot. It was fall and grouse season, late afternoon. One of my brothers came running into the house, saying that there was a grouse behind the log cabin (a shed we used for storage, sided with slab wood).

I grabbed the Village Gun, and loaded a couple of cartridges into the magazine. I was out the door in a few seconds. Grouse, once flushed, will not sit in a tree forever. I carefully approached the referenced spot. I used the shed for cover. Then, stealthily, moving behind it, I searched the trees for the bird. There it was! Sitting in birch tree about 20 feet off the ground. I picked the base of the neck for the shot. The Village Gun was dead on at 15 yards, and the bird fell when the little rifle spat.

The bullet was headed North Northwest, and I knew there were no houses in that direction for miles. Once a .22 bullet hits something, it is almost certainly destabilized. The max range is dramatically reduced.

The bird above is in a crabapple tree. Crab apples are a favorite food for grouse. I regularly checked out crabapple locations when grouse hunting. Much of my grouse hunting was along old logging roads. In many spots, clover had taken root. Clover is another favored grouse food. The old logging roads had areas of exposed gravel, where grouse would obtain the grit they need to grind up their food. I spent far more time on foot, traveling those old logging roads, than I did on pavement on a bicycle.

Growing up on the edge of semi-wilderness spoiled me for a lot of hunting. Being able to grab your rifle and be hunting once you step out the door, is a wonderful thing.

©2016 by Dean Weingarten: Permission to share is granted when this notice is included. Link to Gun Watch

The blue grouse here are about the dumbest bird around. They will sit on a dirt road and let you throw rocks at them.

“Being able to grab your rifle and be hunting once you step out the door, is a wonderful thing.”

Agreed. I lived out in the country for a couple of years in a place just like that.

Ptarmigan (another grouse) gotta be the dumbest. People literally hunt them with clubs.

My grouse hunting in Oregon was fun. We used my dad’s remington .22 pump with a scope to pop them in the head. I’ve also used my great grandmother’s Ithaca 16 Guage double barrel. The birds walked back and forth in the road like a shooting galley as I blasted each one. One other time I was walking down a clear cut and found a grouse by a giant boulder. I was a kid so I decided to follow it around the boulder. I think I made it three times around the rock following the grouse before my dad yelled at me to stop screwing around and deer hunt.

They are pretty tasty. We would fry them up I’m a bit of batter after cutting them into small pieces.

I always used standard velocity .22 solids for small game hunting. High velocity and soft lead hollowpoints can make a mess out of smallish critters you might want to cook.

Thanks for this, I’ve been looking for some world-tested information on the best shot placement on a grouse with a .22

What does grouse taste like…chicken?

No. Hillary Clinton.

(Running away *fast*!)

Slightly gamey chicken. I love the taste of mountain chicken.

‘Nother great article ’bout “days-gone-by” from the “Dean”!

Awesome!

Were they tasty?

I take about 30 ruffed a year for food. Ate 6 last month 2016. From my experience in the coastal mountains they taste better earlier in the season. By December the taste is a bit stronger. They seem to more jumpy at that time as well.

Best cook is real butter on a hot grill, long enough to caramelize the outside but leave the inside on the raw. otherwise it gets tough. Let is sit in the pan off the stove to finish the cook, making sure the meat does not get overdone.

I have a beef with the hunting regulations of taking game birds where I hunt. That the way of cleaning the bird in the field, “breasting” is not allowed. For those that don’t know what that is, it is removing the breast meat from the carcass. Law states head and one wing must be left on bird. That sounds great until you hunt them in the warmer weather and are camping. If you can not keep them cool they get nasty. I have seen more hunters in my life shoot these birds only to throw them out at the end of a hot day. Waste. Just being allowed to bone them out, put them in a plastic bag and toss them in a cooler would eliminate this issue. Many do that anyway. Especial if out for a week. Its the only way to ensure not wasting the meat. Yet, illegal.

Now, the law is supposedly so you can not disguise species. Yeah, there are guys who live in areas where certain birds are protected. But in most of the western coastal highlands you don’t have that problem. There are only 2 game birds that resemble a grouse and they are mountain quail and valley quail. Both of which are half the size or less than a grouse and can not be easily disguised from a grouse even though the meat is breasted.

Once you get over the Cascades then it’s a legit law. Ptarmigan are protected in most units as well as sex restrictions on birds. A guy could take over the limit of one species, but claim his daily bag limit is actually chukar and grouse. west of the Cascades there are no Chukar to speak of. At least in Oregon. There are only grouse and quail. Other game birds meat looks so different that it can’t be confused by any experienced game officer.